Reflection: Greil Marcus

I joined the Riggio program in Writing and Democracy in 2007, and with the exception of 2008 have taught in the program every fall semester since. My main responsibility has been the ULEC undergraduate lecture course “The Old Weird America—Music as Democratic Speech, from the Commonplace Song to Bob Dylan.” The theme of the class, which enrolls between 90 and 100 students, with the participation of four to five Writing Program TAs, is the American folk song—including ballads, blues, blackface minstrelsy, and so-called folk-lyric compositions, where hundreds of floating verses or single lines move from tune to tune, combined by the performer in his or her own way—the sort of song that, regardless of actual provenance, has entered vernacular culture as authorless, with specific origins either lost or forgotten, so that it becomes the common property of anyone who chooses to address it. As such songs are at once traditional and subject to subtle or radical revision by the performer (compare the basic version of the “Titanic” ballad with the 1927 version by the New Orleans street singer Rabbit Brown, where the traditional lyrics are completely transformed by the manner in which they are sung, to Bob Dylan’s 1966 “Desolation Row,” where the Titanic appears along with a host of other cultural signifiers), thus providing the singer access to a shared field of conversation while allowing him or her to say what has never been said, in a manner that has never been heard.

Through readings that include novels (Colson Whitehead’s John Henry Days, Lee Smith’s The Devil’s Dream, Percival Everett’s Erasure), essays (Luc Sante on Bob Dylan and blues, Robert Cantwell on the 60s folk revival and the history of the song “Tom Dooley”), and historical studies (Michael Lesy’s Wisconsin Death Trip, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, Volume 1, the anthology The Rose and the Briar: Death, Love and Liberty in the American Ballad), as well as films, videos, old and new audio recordings (especially those collected on Harry Smith’s “Anthology of American Folk Music”), live performances, either by students or invited guests, and appearances by artists whose work makes up part of the course (over the years, the filmmakers Christian Marclay, Todd Haynes, and James Marsh, the musician Jon Langford, and the novelist Lee Smith), the course is meant to dramatize the notion of the American folk song, ancient and modern, as a form that allows a citizen access to a language anyone can speak and that anyone can understand while at the same time offering the citizen the opportunity to speak altogether as himself or herself, at once attaching the speaker to a common story and allowing the speaker to transform it. The form is democratic; the results are democratic; the form allows the citizen to step out of Tocqueville’s crowd—in this case, history—say what he or she has to say, and then return to anonymity or take his or her story as far as it might travel, in terms of time, space, and audience.

The course encourages students to rewrite and re-envision folk songs discussed in detail in the class, to compose their own and record or perform them, in any medium. In discussion sections, each student takes a character, real or fictional, from life or from a song, mentioned in Bob Dylan’s Chronicles—a vast compendium of such references—and presents that character (which can be a person, a city, a ghost, a story) to his or her section, telling its history, offering an historical representation of it (a photograph, a painting, a recording), and then translating the character into a representation of the student’s own choice (an animated video, a collage, a wardrobe, a painting, a performance, a poem, a short story, a new song). This has, over the years, produced extraordinary and unforgettable results, with the most striking work presented during lectures to the entire class.

Here is a video by Gabi Degirolami (2012), whose TA was Amy Kurzweil, of the 1958 Link Wray recording “Rumble,” cited by Bob Dylan as central to his own “numerical” understanding of the nature of musical communication.

Gabi Degirolami, “Rumble”

Sara Beck, “Ballad of Kate Malone” (2011). Sara was a TA in my first year, in 2007. As Lee Smith’s The Devil’s Dream, one of the novels central to my course, begins with the lyrics to an invented ballad about the first main character in the book, which is set, in a blind manner, to the melody of the folk song “Black Jack Davy,” I have, each year, asked a different person—a TA, a student—to work up an arrangement of the song based in that melody and perform it as part of the lecture keyed to the novel. Sara recorded this version for use when no other candidate presented herself or himself.

In 2009, Madelyn Deutch (TA: Mary Elizabeth Frandon) sang the song. Here, from her final paper, is her account of her performance:

Madelyn Deutch, “Life’s a Bitch, Duck,” comparison between “Black Jack Davy” and “Pretty in Pink”

How can you compare a four-minute song to a major motion picture? It took a writer to pitch, a studio to finance, a director to direct, actors to interpret, a cinematographer to film, a crew of PA’s and grips for the nuts and bolts, an editor to cut, and audience members to view—in order for those emotions to be transferred and the story to be told. It just requires a singer and a guitar, who are willing, to tell the tale of Black Jack Davy. Or in my case, just a singer. I can say with all certainty that “Black Jack Davy” is incomparable to “Pretty in Pink.” Just as neither subtracts from the other, neither goes further or deeper. I know because when I sang in the lecture that week, I felt all of the things that I felt watching the film: sadness, despair, greed, triumph, elation. Even though I was singing different lyrics, I heard the story of Black Jack Davy on a reel in my head. And besides, a melody is a beautiful thing. It’s like sense memory. If you feel one thing while hearing a melody, you feel it again the next time you hear it. And so as I walked up to the front of the room, the last ounce of daylight seeping in through the big rippled windows, I felt the classroom melt around me. The walls became an expanse of forest, with huge pines popping up in corners of the room. The dry wood floors beneath my feet turned to soft earth that gathered up under my heels. I could see fireflies darting in and out of the fol- up chairs that had become tree stumps, overgrown mushrooms, and beds of wildflowers. The cold winter air became misty, as hot and damp as it would have been on a late summer’s eve. I turned to face the audience and I saw a modest cabin, tucked behind the largest pine. A wife, her baby, and a loving father were drifting off to sleep on the porch. I heard the enchanting tune of “Black Jack Davy” dancing in my head, coming closer into the woods. As I slid over notes, bending to sing the sorrow, I watched the cabin go up in flames while the wife followed the tune, utterly hypnotized. But who knows—maybe the next time I sing “Black Jack Davy” I’ll see Duckie flailing and dancing on the staircase in ‘Trax’ and Andie perched by the cash register rolling her eyes. The real beauty in all of this is that, even if I had taken the lyrics I sang in class (“The Ballad of Kate Malone”) literally, it would still complement Pretty in Pink. In the “Malone” version of “Black Jack Davy,” Kate Malone falls in love with a preacher’s son, he promises her salvation, and then she[I’ll check quotation and embed.] loses “her merry laugh… was like to lose her beauty… tied back her hair of purest gold, bore three babes out of duty . . . It would be the equivalent to the wife staying with the husband, avoiding Black Jack Davy, and being miserable. A little known fact is that the original ending for Pretty in Pink had Andie ending up with Duckie instead of Blane. So it seems that “Black Jack Davy” and “Pretty in Pink” are endlessly connected! And there appears the beautiful phenomenon that there are no coincidences in this world.

In 2007, Nina Torr created “Tom Dooley Animation,” a video scored to the Kingston Trio’s 1958 version of the folk song, several versions of which were part of the class, that enacted a tall tale from Constance Rourke’s “American Humor: A Study of the National Character” (1931), which was part of the required reading that year.

Here, from 2010, is Jesse Valentine’s discussion-section essay “How to Write an American Folk Song,” as later read to the whole class (TA: Jaclyn Lovell)

Jesse Valentine (Jaclyn Lovell) reads “How to Write an American Folk Song”:

First, make a list of the list of the parts of your body that no longer work. Put it in an envelope. Mail it to your mother. Have her write the name she would have given her next child across the top of it. Have her mail it back to you. Every night before sleeping, kneel by your bedside, hold it your hands, read it aloud.

Second, track down the girl you loved in the eighth grade. Give her a mix CD of all your favorite songs from 2003. Ask her to learn the words to each one, and to record herself singing them a capella onto a tape recorder. Have her send you that tape. With a black magic marker write memories across it. Keep it in your car. Make it the only thing you listen to when you drive.

Third, become a terrorist. Hide a box-cutter in your shoe and board an airplane, but don’t do anything. Just know that you could be in control and you’re choosing not to be. Think about what that means. Write a poem about it. Send it to The New Yorker, and don’t ever throw away the rejection letter.

Fourth, start smoking again. Who are you trying to fool? You know you’re going to start smoking again anyway, so why not start again now? On each one of your rolling papers, write the name of the town where you were born, so that every time you smoke you can watch it burn down. Call this forgiveness.

Fifth, find a field, dig a hole, get inside it. Pile the dirt back in on top of yourself. If you get down deep enough you can talk to the dead. If you see your grandfather tell him you’re doing okay, even if you’re not. It’s all he wants to hear. Give him that.

Sixth, don’t let go of my hand. Climb a tree with me. Sit on a branch. Walk by the water with me. Throw me at the waves like a fisherman’s prayer. If I tell you I don’t believe in God anymore, tell me you still do.

Seventh, buy a banjo. Learn a chord. Take all of these things and turn them into a song. Record it. And makes sure no one listens to it till long after you’re dead. Rest easy, someday it’ll be all that’s left of you.

Brianne Bowers, “Like a Rolling Stone” and “The Coo Coo” by Be Good Tanyas—in 2010, this student made two videos for the class, the first based on the idea that the inspiration for “Like a Rolling Stone” was the Warhol superstar Edie Sedgewick, the second on the 2000 version of “The Coo Coo” by Be Good Tanyas, before knowing that I planned to build my lecture on the song around that version:

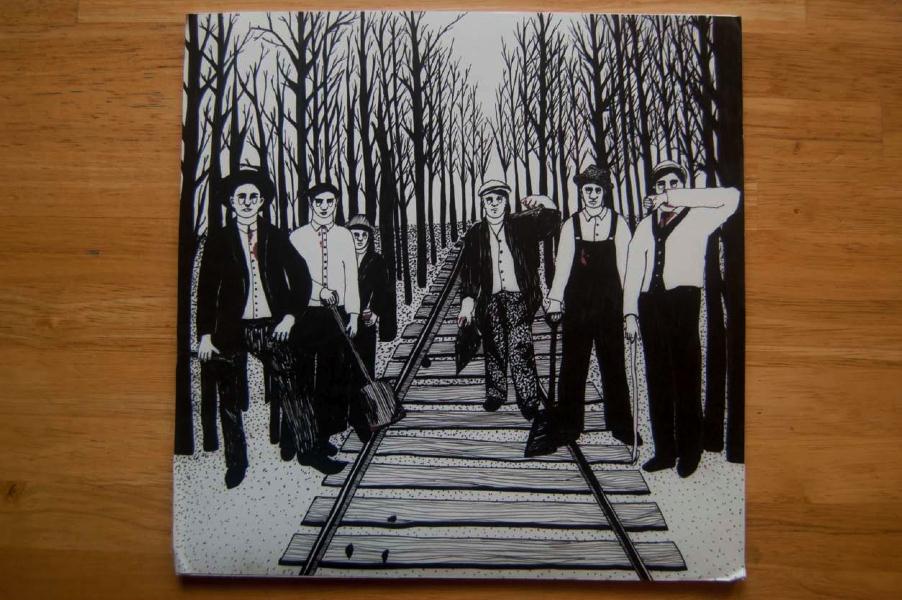

Also in 2010, Sofia Falcone created this depiction of the verse in “I Wish I Was a Mole in the Ground,” an axis of the course, that runs, “I don’t like a railroad man / No, I don’t like a railroad man /A railroad man, he’ll kill you when he can / And drink up your blood like wine,” in the form of an LP jacket.

I could include many more papers, and there is visual work I have not been able to convert or that is unavailable on the Internet. But this should give you some idea of the kind of undergraduate work that has come out of the class.

The effect of student work on my own work has been incalculable. I learn (over and over again), what I don’t know, what I haven’t seen. Songs that I have heard hundreds of times and written about in great detail are explicated or dramatized in ways that make it seem as if I have never heard them at all, and the same is true for the reading in the course, whether essays or novels. Most of all, I discover that the premise of the course, explained most fully and explicitly in Dylan’s “Chronicles” (“A folk song has over a thousand faces and you must meet them all”) is more true than I could have ever imagined: that there is no limit whatsoever on what folk songs can say, where they can go, who can sing them, and what secrets they contain.

My experiences in the Riggio program have affected my teaching by leading me to be more experimental, improvisational, to take little for granted. Given the pedagogical nature of the class, in terms of the American folk song as a field for expression, I have always thought that the purpose of the class was to lead students to find, value, and use their own voices, certainly never to offer a particular point of view for their agreement, and I hope that I pursue this more vigorously each year.

And finally, from 2012, Pavla Kostich, insect-infested dress inspired by Wisconsin Death Trip (TA: Carrington Alvarez)

As part of my charge in the Riggio program, I also curate a lecture series each semester. Four people in the arts, or in various fields in the humanities, are invited to give a public talk on culture, audience, tradition, and transformation. Speakers in 2012 included the jazz critic and biographer Stanley Crouch, the theatre critic and biographer Hilton Als, the music critic Ann Powers, and the blues historian Marybeth Hamilton. Previous speakers have included the novelists Walter Mosley, Mary Gaitskill, and Dana Spiotta, the critic and historian Luc Sante, and the musician and writer David Thomas.

This year, in a partnership between the Writing Program and Liberal Studies, I also taught a graduate seminar component of the “Old Weird America” course. Fourteen graduate students attended the lectures, and then after a short break we discussed the readings that make up the body of the class, along with music and films, from completely different vantage points than the lectures explore. It was a close-knit group of students of varying backgrounds—with people very vehement about their backgrounds, and the value of different frames of reference in any discussion. There was one student from South Africa, two from Norway, one from North Carolina, one from rural West Virginia, and on from there—a very disparate group of people who very quickly came to trust each other as adventurers in a common quest. From the start, students were bringing in music, videos, and even performing their own work in order to make arguments and raise questions. Their writing, in the first assigned paper, was so superb—experimental in form, daring in argument, carefully written, resistant to conventional wisdom, sometimes coming out of deep familiarity with the material of the class, sometimes with none—that I assigned a full paper every two weeks, and the quality improved every week. Often the papers—which the students began circulating among each other before I was about to suggest it—formed the basis of discussions, but sometimes a single comment from one student would occupy the entire 90-minute class. Except for one graduate seminar at Berkeley, this was the best class I have ever had. It was not about Writing and Democracy, it was writing and democracy, in action. I would happily provide more student work, from different years, if that would be useful. I am attaching a piece that, I hope, is fitting for the theme we are attempting to bring out to the full. It has been my great privilege to be part of the Writing and Democracy program and I hope it continues in full force for a very long time.

Read Greil Marcus’s “A Trip to Hibbing High,” and a profile of him.

Greil Marcus was an early editor at Rolling Stone, and has since been a columnist for Salon, the New York Times,Artforum, Esquire, and the Village Voice; he currently writes a monthly music column for Interview magazine. He is the author of The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (1997), Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (2005), as well as The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice (2006),Lipstick Traces (1989), Mystery Train (1975), The Dustbin of History (1995), Dead Elvis (1991), and other books. With Werner Sollors, he is the editor of A New Literary History of America (2009). In recent years he has taught seminars in American Studies at Berkeley and Princeton.