A Trip to Hibbing High

Greil Marcus

Daedalus Spring 2007

“As I walked out—” Those are the first words of “Ain’t Talkin’,” the last song on Bob Dylan’s Modern Times, released in the fall of 2006. It’s a great opening line for anything: a song, a tall tale, a fable, a novel, a soliloquy. The world opens at the feet of that line. How one gets there—to the point where those words can take on their true authority, raise suspense like a curtain, and make anyone want to know what happens next—is what I want to look for.

For me this road opened in the spring of 2005, upstairs in the once-famous, now shut Cody’s Books on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley. I was giving a reading from a book about Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone.” Older guys—people my age—were talking about the Dylan shows they’d seen in 1965: He had played Berkeley on his first tour with a band that December. People were asking questions—or making speeches. The old saw came up: “How does someone like Bob Dylan come out of a place like Hibbing, Minnesota, a worn-out mining town in the middle of nowhere?”

A woman stood up. She was about 35, maybe 40, definitely younger than the people who’d been talking. Her face was dark with indignation.

“Have any of you ever been to Hibbing?” she said. There was a general shaking of heads and murmuring of nos’s—from me and everyone else. “You ought to be ashamed of yourselves,” the woman said. “You don’t know what you’re talking about. If you’d been to Hibbing, you’d know why Bob Dylan came from there. There’s poetry on the walls. Everywhere you look. There are bars where arguments between socialists and the IWW, between Communists and Trotskyists, arguments that started a hundred years ago, are still going on. It’s there—and it was there when Bob Dylan was there.”

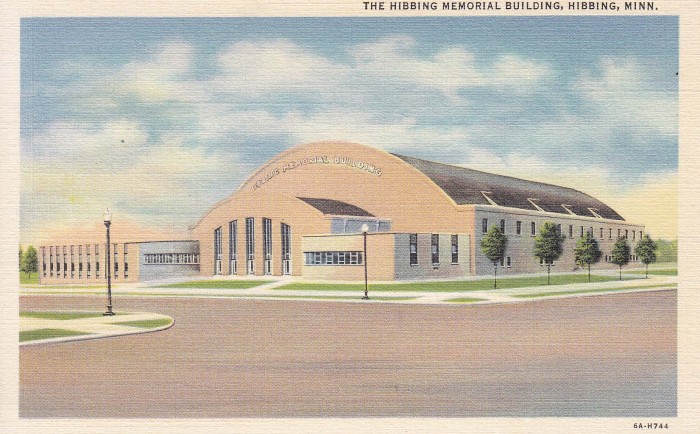

“I don’t remember the rest of what she said,” my wife said when I asked her about that night. “I was already planning our trip.” Along with our younger daughter and her husband, who live in Minneapolis, we arrived in Hibbing a year later, coincidentally during Dylan Days, a now-annual weekend celebration of Bob Dylan’s birthday, in this case his sixty-fifth. There was a bus trip, the premiere of a new movie, and a sort of Bob Dylan Idol contest at a restaurant called Zimmy’s. But we went straight to the high school. On the bus tour the next day, we went back. And that was the shock: Hibbing High.

In his revelatory 1993 essay “When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival,” the historian Robert Cantwell takes you by the hand, guides you back, and reveals the new America that rose up out of World War II. “If you were born between, roughly, 1941 and 1948,” he says—”born, that is, into the new postwar middle class,” you grew up in a reality perplexingly divided by the intermingling of an emerging mass society and a decaying industrial culture . . . Obscurely taking shape around you, of a definite order and texture, was an environment of new neighborhoods, new schools, new businesses, new forms of recreation and entertainment, and new technologies that in the course of the 50s would virtually abolish the world in which your parents had grown up.

That sentence is typical of Cantwell’s style: apparently obvious social changes charted into the realm of familiarity, then a hammer coming down: as you are feeling your way into your own world, your parents’ world is abolished.

Growing up in the certified postwar suburb towns of Palo Alto and Menlo Park in California, I lived some of this life. Though Bob Dylan did not grow up in the suburbs—despite David Hajdu’s dismissal of Dylan, in his book Positively 4th Street, as “a Jewish kid from the suburbs,” Hibbing is not close enough to Duluth, or any other city, to be a suburb of anything—he lived some of this life, too.

Cantwell moves on to talk about how the new prosperity of the 50s was likely paradise to your parents, how their aspirations became your seeming inevitabilities: “Very likely, you saw yourself growing up to be a doctor or a lawyer, scientist or engineer, teacher, nurse, or mother—pictures held up to you at school and at home as pictures of your special destiny.” And, Cantwell says, You probably attended, too, an overcrowded public school, typically a building built shortly before World War I . . . [you] may have had to share a desk with another student, and in addition to the normal fire and tornado drills had from time to time to crawl under your desk in order to shield yourself from the imagined explosion of an atomic bomb.

So, Cantwell writes, “in this vision of consumer Valhalla there was a lingering note of caution, even of dread”—but let’s go back to the schools.

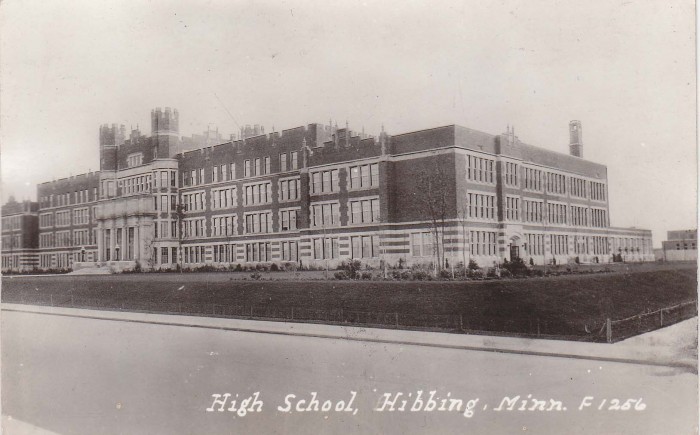

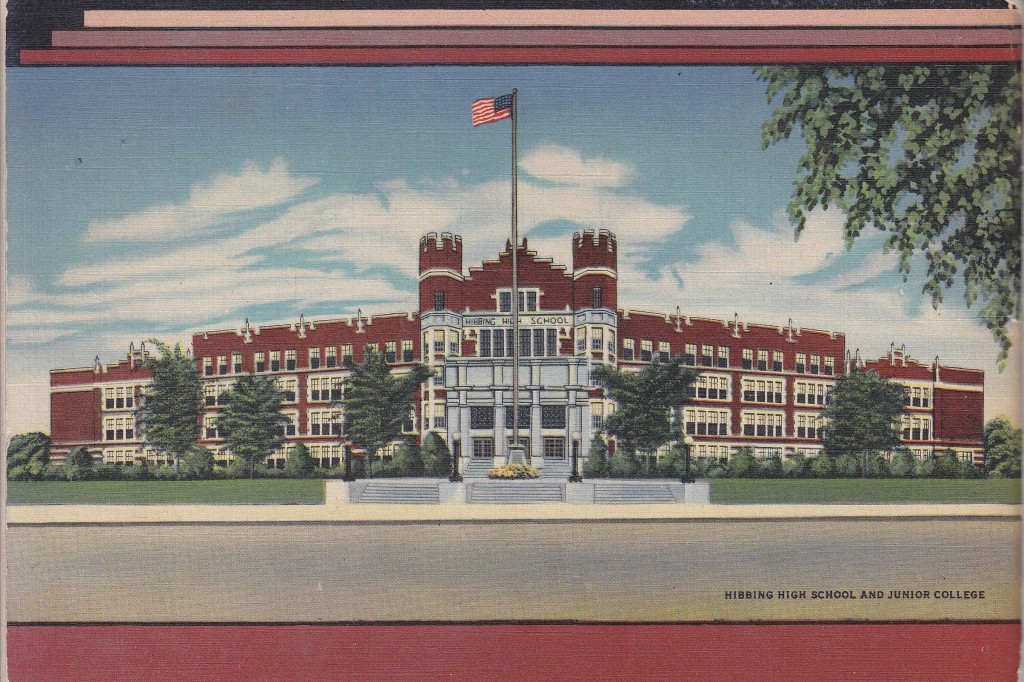

The public schools I attended—Elizabeth Van Auken Elementary School (now Ohlone School) in Palo Alto, and Menlo Atherton High School in Menlo Park—were not built before World War I. They were built in the early ’50s, part of the world that was already changing. The past was still there: Miss Van Auken, a beloved former teacher, was always present to celebrate the school’s birthday. When our third-grade class read the Little House books, we wrote Laura Ingalls Wilder and she wrote back. But the past was fading as new houses went up all around the school. A few miles away, Menlo-Atherton High was a sleek, modern plant: one story, flat roofs, huge banks of windows in every classroom, lawns everywhere, and three parking lots, one reserved strictly for members of the senior class. The school produced Olympic swimmers in the early 60s; a few years later Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks would graduate and, a few years after that, make Fleetwood Mac the biggest band in the world. The school sparkled with suburban money, rock ‘n’ roll cool, surfer swagger, and San Francisco ambition—and compared to Hibbing High School it was a shack. “I know Hibbing,” Harry Truman said in 1947, when he was introduced to Hibbing’s John Galeb, the National Commander of Disabled American Veterans. “That’s where the high school has gold door knobs.”

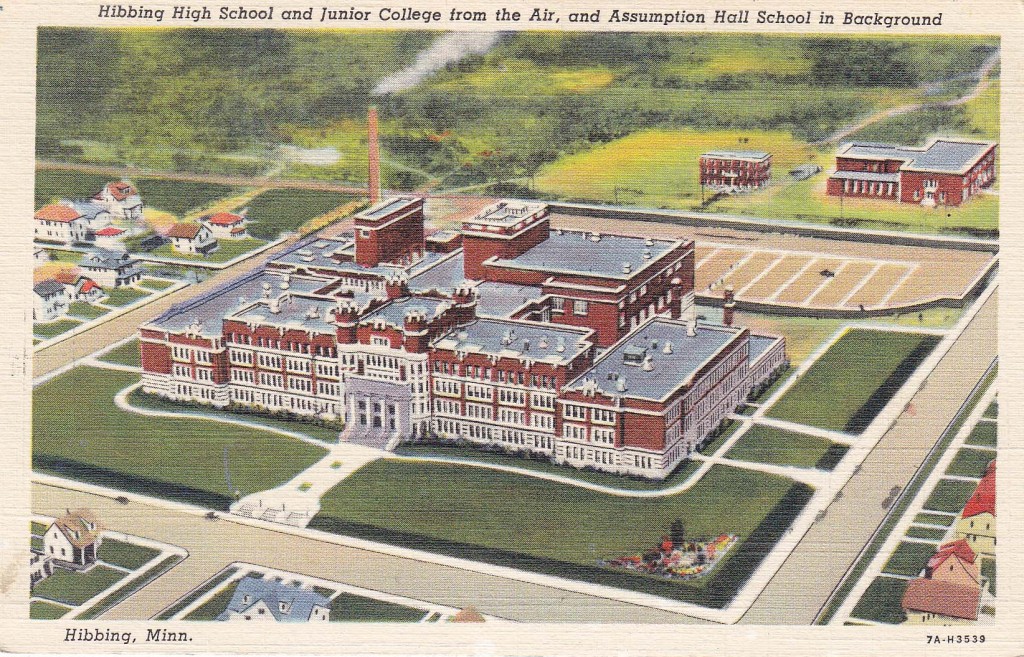

Outside of Washington, D.C., it’s the most impressive public building I’ve ever seen. In aerial photographs, it’s a colossus: four stories, 93 feet high, with wings 180 feet long flying out from a 416-foot front. From the ground it is more than anything a monument to benign authority, a giant hand welcoming the town, all of its generations, into a cave where the treasure is buried, all the knowledge of mankind. It speaks for the community, for its faith in education, not only as a road to success, to wealth and security, reputation and honor, but as a good in itself. This town, the building says, will have the best school in the world.

In the plaza before the building there is a spire, a war memorial. On its four sides, as you turn from one panel to another, are the names of those students from Hibbing who died in the First World War, the Second World War, the Korean and Vietnam Wars—and, on the last panel, with no names, a commemoration of the terrorist attacks of 2001. Past the memorial are steps worthy of a state capitol leading to the entrance of the building. It was late Friday afternoon; there were no students around, but the doors were open.

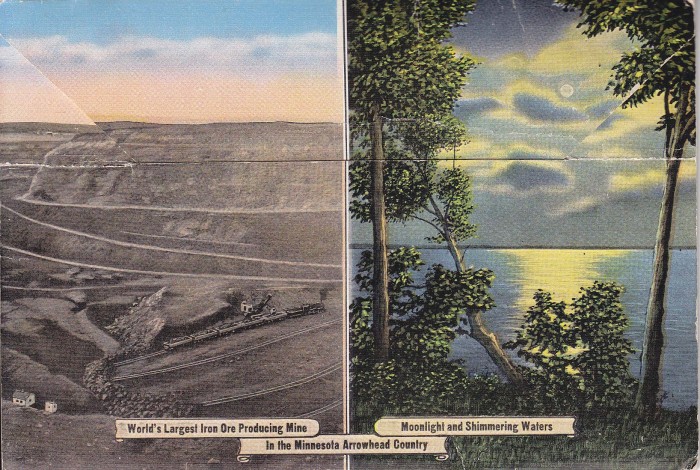

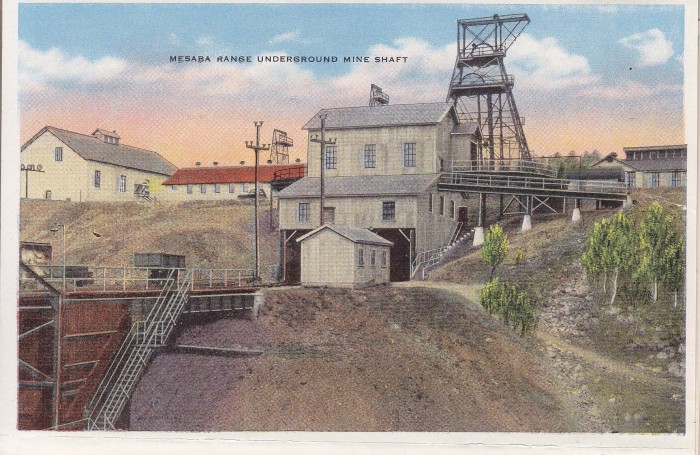

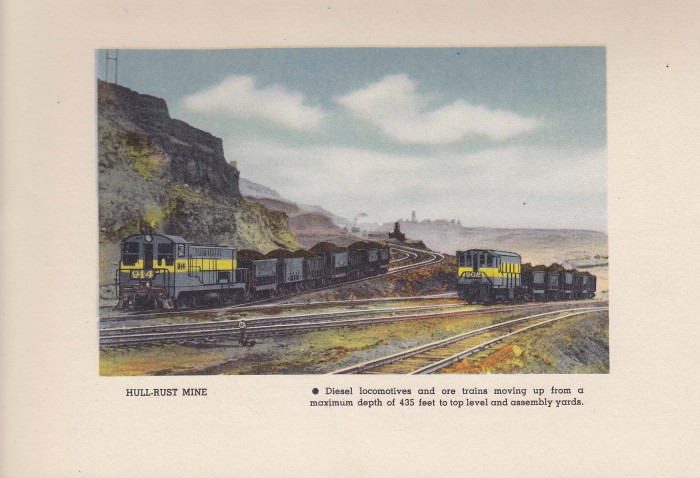

Hibbing High School was built near the end of the era when Hibbing was known as “the richest village in the world.” A crusading mayor, Victor Power, enforced mineral taxes on US Steel, operator of the huge iron-ore pit mines that surrounded the original Hibbing. Elected after a general strike in 1913, he fought off the mine company’s allies in the state legislature and the courts in battle after battle. When ore was discovered under the Hibbing itself, Power and others forced the company to spend sixteen million dollars to move the whole town—houses, hotels, churches, public buildings—four miles south. The bigger buildings were cut in quarters and reassembled in the new Hibbing like Legos.

Tax revenues had mounted over the years in the old north Hibbing; at one point, the story goes, when a social-improvement society took up donations for poor families, none could be found. But in the new south Hibbing, in a maneuver aimed at building support for lower corporate tax rates in the future, the mining company offered even more money in the form of donations, or bribes: school-board members directed most of it to what became Hibbing High, which Mayor Power had demanded as part of the price of moving the town. With prosperity seemingly assured, the town turned out Victor Power in favor of a mayor closer to the mines. Soon a law was passed limiting public spending to a hundred dollars per capita per year; then the limit was lowered, and lowered again. The tax base of the town began to crumble; with World War II, when the town was not allowed to tax mineral production, and after, when the mines were nearly played out, the tax base all but collapsed. Ultimately, the mines shifted from iron ore to taconite, low-grade pellets that today find a market in China, but Hibbing never recovered. In the 50s it was a dying town, the school a seventh wonder of a time that had passed, a ziggurat built by a forgotten king. And yet it was still a ziggurat.

When it opened in 1924, Hibbing High School had cost four million dollars, an unimaginable sum for the time. At first it was the ultimate consolidated school, from kindergarten through junior college. There were three gyms, two indoor running tracks, and every kind of shop that in the years to come would be commonplace in American high schools—as well as an electronics shop, an auto shop, a conservatory. There was a full-time doctor, dentist, and nurse. There were extensive programs in music, art, and theater. But more than eight decades later, you didn’t have to know any of this to catch the glow of the place.

Climbing the enclosed stairway that followed the expanse of outdoor steps, we saw not a hint of graffiti, not a sign of deterioration in the intricate colored tile designs on the walls and the ceilings, in the curving woodwork. We gazed up at old-fashioned but still majestic murals depicting the history of Minnesota, with bold trappers surrounded by submissive Indians, huge trees and roaming animals, the forest and the emerging towns. It was strange, the pristine condition of the place. It spoke not for emptiness, for Hibbing High as a version of Pompeii High—though the school, with a capacity of over 2,000, was down to 600 students, up from four hundred only a few years before—and, somehow, you knew the state of the building didn’t speak for discipline. You could sense self-respect, passed down over the years.

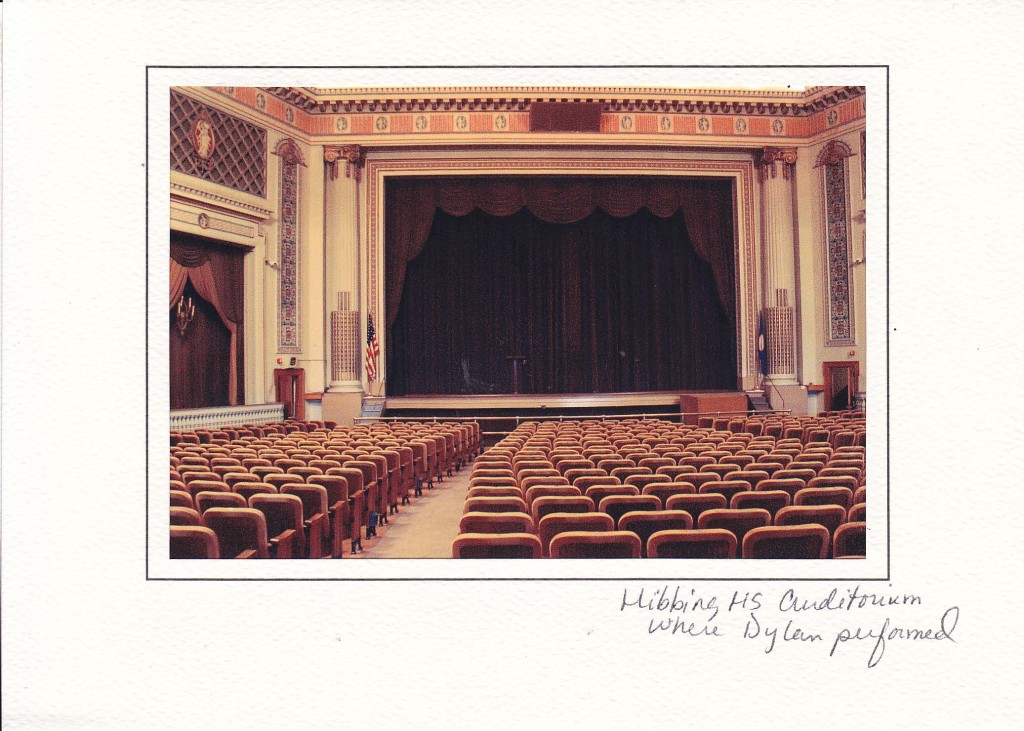

We followed the empty corridors in search of the legendary auditorium. A custodian let us in, and told us the stories. Seating for 1,800, and stained glass everywhere, even in the form of blazing candles on the fire box. In large, gilded paintings in the back, the muses waited; they smiled over the proscenium arch, too, over a stage that, in imitation of thousands of years of ancestors, had the weight of immortality hammered into its boards. “No wonder he turned into Bob Dylan,” said a visitor the next day, when the bus tour stopped at the school, speaking of the talent show Dylan played here with his high-school band the Golden Chords. Anybody on that stage could see kingdoms waiting.

There were huge chandeliers, imported from Czechoslovakia, four thousand dollars each when they were shipped across the Atlantic in the 1920s, irreplaceable today. We weren’t in Hibbing, a redundant mining town in northern Minnesota; we were in the opera house in Buenos Aires. Yet we were in Hibbing; there were high-school Bob Dylan artifacts in a case just down the hall. There were more in the public library some blocks away, in a small exhibit in the basement. Scattered among commonplace talismans, oddities and revelations were the lyrics to Golden Chords’ “Big Black Train,” from 1958, a rewrite of Elvis’s 1954 “Mystery Train,” credited to Monte Edwardson, LeRoy Hoikkala, and Bob Zimmerman:

Well, big black train, coming down the line

Well, big black train, coming down the line

Well, you got my woman, you bring her back to me

Well, that cute little chick is the girl I want to see

(Chorus)

Well, I’ve been waiting for a long long time

Well, I’ve been waiting for a long long time

Well, I’ve been looking for my baby

Searching down the line

(Second verse)

Well, here comes the train, yeah it’s coming down the line

Well, here comes the train, year it’s coming down the line

Well, you see my baby is finally coming home

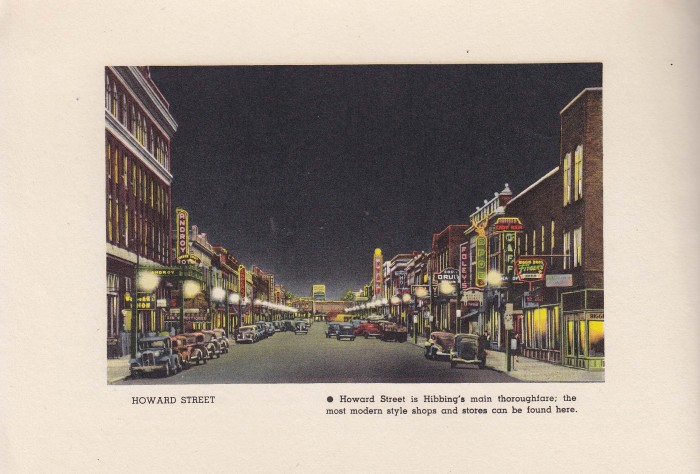

The next day, walking up and down Howard Street, the main street of Hibbing, we looked for the poetry on the walls. “A NEW LIFE,” read an ad for an insurance company—was that it? Was there anything in that beer sign that could be twisted into a metaphor? What was the woman in Berkeley talking about? Later we found out that the walls with the poetry were in the high school itself.

In the school library there were busts and chiseled words of wisdom and murals. Murals told the story of the mining industry, all in the style of what Daniel Pinkwater, in his young-adult novel Young Adults, called “heroic realism.” There were sixteen life-size workers, representing the nationalities that formed Hibbing: native-born Americans, Finns, Swedes, Italians, Norwegians, Croatians, Serbs, Slovenians, Austrians, Germans, Jews, French, Poles, Russians, Armenians, Bulgarians, and more. There was a huge mine on the left, a misty steelworks on the right, and, in the middle, to take the fruit of Hibbing to the corners of the earth, Lake Superior. With art-nouveau dots between each word, the inscription over the mine quoted Tennyson’s “Oenone”:

LIFTING•THE•HIDDEN•IRON•

THAT•GLIMPSES•IN•LABOURED•

MINES•UNDRAINABLE•OF•ORE

—while over the factory one could read

THEY•FORCE•THE•BURNT•

AND•YET•UNBLOODED•STEEL•

TO•DO•THEIR•WILL

That was the poetry on the walls—but not even this was the real poetry in Hibbing. The real poetry was in the classroom.

A fter stopping by the auditorium and the library, the tours made its way upstairs to Room 204, where for five years in the 50s, B. J. Rolfzen taught English at Hibbing High—after that, he taught for 25 years at Hibbing Community College. Eighty-three in May of 2006, and slowed down by a stroke, getting around in a motorized wheelchair, Rolfzen sat on the desk in the small, suddenly steamy room, as forty or more people crowded in. There was a small podium in front of him. Presumably we were there to hear his reminiscences about the former Bob Zimmerman—or, as Rolfzen called him, and never anything else, Robert. Rolfzen held up a slate where he’d chalked lines from “Floater,” from Dylan’s 2001 “Love and Theft”: “Gotta sit up near the teacher / If you want to learn anything.” Rolfzen pointed to the tour member who was sitting in the seat directly in front of the desk. “I always stood in front of the desk, never behind it,” he said. “And that’s where Robert always sat.” He talked about Dylan’s “Not Dark Yet,” from his 1997 Time Out of Mind: “‘I was born here and I’ll die here / Against my will.'” “I’m with him. I’ll stay right here. I don’t care what’s on the other side,” Rolfzen said, a teacher thrilled to be learning from a student. With that out of the way, he proceeded to teach a class in poetry.

fter stopping by the auditorium and the library, the tours made its way upstairs to Room 204, where for five years in the 50s, B. J. Rolfzen taught English at Hibbing High—after that, he taught for 25 years at Hibbing Community College. Eighty-three in May of 2006, and slowed down by a stroke, getting around in a motorized wheelchair, Rolfzen sat on the desk in the small, suddenly steamy room, as forty or more people crowded in. There was a small podium in front of him. Presumably we were there to hear his reminiscences about the former Bob Zimmerman—or, as Rolfzen called him, and never anything else, Robert. Rolfzen held up a slate where he’d chalked lines from “Floater,” from Dylan’s 2001 “Love and Theft”: “Gotta sit up near the teacher / If you want to learn anything.” Rolfzen pointed to the tour member who was sitting in the seat directly in front of the desk. “I always stood in front of the desk, never behind it,” he said. “And that’s where Robert always sat.” He talked about Dylan’s “Not Dark Yet,” from his 1997 Time Out of Mind: “‘I was born here and I’ll die here / Against my will.'” “I’m with him. I’ll stay right here. I don’t care what’s on the other side,” Rolfzen said, a teacher thrilled to be learning from a student. With that out of the way, he proceeded to teach a class in poetry.

He handed out a photocopies booklet of poems by Wordsworth, Frost, Carver, the Minneapolis poet Colleen Sheehy, and himself; moving back and forth for more than half an hour, he returned again and again to the eight lines of William Carlos Williams’s “The Red Wheelbarrow.”

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chicken

He kept reading it, changing inflections, until the words seemed to dance out of order, shifting their meanings. Each time, a different word seemed to take over the poem. “Rain,” he would say, opening up the poem one way; “beside,” he’d say, and an entirely different drama seemed underway. Finally he came full circle. “‘so much depends / upon a red wheel / barrow,'” he said. “So much depends. This isn’t about rain. It’s not about chickens. So much depends on the decisions we make. My decision to enlist in the Navy in 1941, when I was 17. My decision to teach. So much depends on the decisions you’ve made, and will make.”

The poem stayed in the air: The loudness of the first line faded into “beside the white chickens,” not because they were unimportant, but because from “so much depends,” from the decision with which the poem began, the poem, like a life, could have gone anywhere; it was simply that in this case the poem happened to go toward chickens, before it went off the page, to wherever it went next. Rolfzen made the eight lines particular and universal, unlikely and fated; he made them apply to everyone in the room, or rather led each person to apply them to him or herself. This was not the sort of teacher you encounter everyday—or even in a lifetime.

“Bits and pieces of the Great Depression still lie about,” Rolfzen wrote in The Spring of My Life, a memoir of the 1930s he published himself in 2005—but he said, “The experiences and frightful hopelessness of one day of The Great Depression can never be understood or appreciated except by those who have lived it.” Nevertheless, he tried to make whoever might read his book understand. He went back to the village of Melrose, Minnesota, where he was born and grew up. He spoke quietly, flatly, sardonically of a family that was poor beyond poverty: “Life during the Great Depression was not a complex life. It was a simple one. No health insurance needed to be paid, no life insurance, no car insurance, no savings for a college education or any education beyond high school, no savings account, no automobile needed to be purchased, no gas was necessary to buy, no utilities beyond the $3.00 a month my dad paid for six 25 watt bulbs.” There were eleven children; B. J.—then Boniface—slept in a bed with three brothers.

His father was an electrical worker and a drunk: the “most frightening day,” Rolfzen writes, was payday, when his father would stagger home, then and every day until the money ran out. One day he tried to kill himself by grabbing high-voltage lines; instead he lost both arms just below the elbow, and sent the family onto relief. “I never saw my mother with a coin in her hand,” Rolfzen writes; everything they bought they bought on credit against 50 dollars a month. There was a family of four that boarded up the windows of its house to keep out the cold, but the Rolfzens would not advertise their misery, even if the windows sometimes broke and, before they could be replaced, maybe not until winter passed, maybe not for months after that, snow piled up in the room where Rolfzen slept.

All through the book, through its continual memories of privation and idyll—of catching bullheads, playing marbles, picking berries, working on a farm for three months at the age of sixteen for four cents a day, or the toe of a young Boniface’s shoe falling off as he walked to school—one can feel Rolfzen holding his rage in check. His rage against his father, against the cold, against the plague that was on the land, against the alcoholism that followed from his father to his brothers, against the Catholic elementary school he was named for, St. Boniface, run by nuns who “enjoyed causing pain,” a place where students were threatened with hell for every errant act—where religion “was a senseless, heartless and unforgiving practice. I still bear its scars.”

“In times behind, I too / wished I’d lived / in the hungry Thirties,” Bob Dylan wrote in 1964 in “Eleven Outlined Epitaphs,” his notes to The Times They Are A-Changin’. “Rode freight trains for kicks / Got beat up for laughs / I was making my own depression,” he wrote the year before in “My Life in a Stolen Moment”—speaking of leaving Hibbing, leaving the University of Minnesota, traveling west, trying to learn how to live on his own. “I cannot remember ever having a conversation with my dad about anything,” Rolfzen writes—but you can imagine him having conversations about the 30s with Robert. Maybe especially about the tramp armies that passed through Melrose, starting every day at ten when the train pulled in, 20 men or more riding on top of the box cars, jumping from the doors, men who had abandoned their families, who broke into abandoned buildings and knocked on the Rolfzens’ back door begging for food—”My mother never refused them,” Rolfzen writes. With whatever they could scavenge, they headed to a hollow near the tracks, the place called the Bums’ Nest or the Jungle. As a boy, Rolfzen was there, watching and listening, but he will not allow a moment of romance, freedom, or escape: “Theirs was a controlled camaraderie with limited laughter. Each man was alone on these tracks that led to nowhere . . . And so they left. More would arrive the next day. One gentleman in particular I remember. An old bent man dressed in a long shabby coat, a tattered hat on his head and a cane in his hand. The last time I saw him, he was headed west along the railroad tracks, headed for an empty world.”

This is not how the song of the open road goes—and while Bob Dylan has sung that song as much as anyone, as the road opened it also forked, even from the start. “At the end of the great English epic Paradise Lost,” Rolfzen writes, “Milton observes the departure of Adam and Eve from the Garden, and as he observes their leaving by the Eastern Gate, he utters these beautiful words: ‘The world was all before them.'” So much depends—think of “Bob Dylan’s Dream,” from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, in 1963. There he is, twenty-two, “riding on a train going west,” dreaming of his true friends, his soulmates—and then suddenly he is an old man. He and his friends have long since vanished to each other. Their roads haven’t split so much as crumbled, disappeared—”shattered,” he sings. How was it that, in 1963, his voice and guitar calling up a smoky, out-of-focus portrait, Bob Dylan was already looking back, from forty, fifty, sixty years later? “

“As I walked out . . .” With those first words for “Ain’t Talkin'”—not only the longest song on Modern Times, and the strongest, but the only performance on the album where you don’t hear calculation—Bob Dylan disappears. Someone other than the singer you think you know seems to be singing the song. He doesn’t seem to know what effects to use, what they might even be for. It’s the only song on the album, really, without an ending—and with those first four words, a cloud is cast. The singer doesn’t know what’s going to happen—and it’s the way he expects that nothing will happen, the way he communicates an innocence you instantly don’t trust, that steels you for the story that he’s about to tell, or that’s about to sweep him up. He walks out into “the mystic garden.” He stares at the flowers on the vines. He passes a fountain. Someone hits him from behind.

This is when he finds the world all before him—because he can’t go back. There is only one reason to travel this road: revenge.

For the only time on Modern Times, the music doesn’t orchestrate, doesn’t pump, doesn’t give itself away with its first note. Led by Tony Garnier’s cello and Donnie Herron’s viola, the band curls around the singer’s voice even as he curls around the band’s quiet, retreating, resolute sound, as if the whole song is the opening and closing of a fist, over and over again, the slow rhythm turning lyrics that are pretentious, even precious on the page into a kind of oracular bar talk, the old drunk who’s there every night and never speaks finally telling his story. “I practice a faith that’s long abandoned,” he says, and that might be the most frightening line Bob Dylan has written in years. “That’s been destroyed,” Dylan told Doon Arbus in 1997, speaking of “the secret community” of “like-minded people” he found in the early ’60s, a fellowship of those who felt themselves “outside and downtrodden,” a community that “spread out across America”—”I don’t know who destroyed it.”

“I know, in my mind, I’m still a member of a secret community. I might be the only one,” Dylan said then; in “Ain’t Talkin'” the singer moves down his road of patience and blood. You can sense his head turning from side to side as he tells you why his head is bursting: “If I catch my opponents ever sleeping / I’ll just slaughter ’em where they lie.” He snaps off the line casually, as if it’s hardly worth the time it takes to say, as if he’s done it before, like William Munny in Unforgiven killing children on his way to wherever he went, but that will be nothing to what the singer do to get wherever it is he’s going. God doesn’t care: “the gardener,” the singer says to a woman he finds in the mystic garden, “is gone.”

Now, Bob Dylan didn’t need B. J. Rolfzen’s tales of the tramp armies that passed through Melrose during the Great Depression to catch a feel for “tracks that led to nowhere.” Empathy has always been the genie of his work, of the tones of his voice, his sense of rhythm, his feel for how to fill up a line or leave it half empty, his sense of when to ride a melody and when to bury it, so that it might dissolve all of a listener’s defenses—and this is what allowed Dylan, in 1962 at the Gaslight Café in Greenwich Village, at home in that secret community of tradition and mystery, to become not only the pining lover in the old ballad “Handsome Molly,” but also Handsome Molly herself.

There’s no tracing that quality of empathy to anything—so much depends—but if effects like these had causes, then there would be people doing the same on every corner, in any time. On the way to Hibbing, we stopped at an antique store; shoved in among a shelf of children’s books was a small, cracked book called From Lincoln to Coolidge, published in 1924, a collection of news dispatches, excerpts from Congressional hearings, and speeches, among them the speech Woodrow Wilson gave to dedicate Abraham Lincoln’s official birthplace in Hodgenville, Kentucky, on September 4, 1916—according to the story a young Bob Dylan was told, just weeks before his one-year-old mother was taken by her parents to see the president campaign in Hibbing from the back of a train. “This is the sacred mystery of democracy,” Wilson said that day in Hodgenville, “that its richest fruits spring up out of soils that no man has prepared and in circumstances amidst which they are least expected.”

That is the truth, and that is the mystery. In the case of Bob Dylan, as with any person who does things others don’t do, the mystery is always there. But from the overwhelming fact of the pure size of Hibbing High School, from the ambition and vision placed in the murals in its entryway, from the poetry on the walls to the poetry in the classroom, perhaps to memories recounted after everyone else had gone—or memories picked up by a student from the way a teacher moved, hesitated over a word, dropped hints he never quite turned into stories—these soils were not unprepared at all.

Robert Cantwell, “When We Were Good: Class and Culture in the Folk Revival,” collected in Transforming Tradition: Folk Music Revivals Examined, edited by Neil V. Rosenberg. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois, 1993.

—When We Were Good: The Folk Revival. Cambridge: Harvard, 1996. B. J. Rolfzen, The Spring of My Life. Hibbing, MN: Band Printing, 2004. Bob Dylan, “11 Outlined Epitaphs,” liner notes to The Times They Are A-Changin’ (Columbia, 1964).

—“Bob Dylan’s Dream” from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (Columbia, 1963).

—“Ain’t Talkin’,” from Modern Times (Columbia, 2006).

—“That’s been destroyed.” In Richard Avedon and Doon Arbus, The Sixties. New York: Random House, 1999. 210.

Woodrow Wilson, “Address of Woodrow Wilson at Lincoln’s Birthplace,” collected in From Lincoln to Coolidge, edited by Alfred E. Logie. Chicago: Lyons and Carnahan, 1925.

Read Greil Marcus’s reflection on The Riggio Honors Program: Writing & Democracy, and a profile of him.

Greil Marcus was an early editor at Rolling Stone, and has since been a columnist for Salon, the New York Times, Artforum, Esquire, and the Village Voice; he currently writes a monthly music column for Interview magazine. He is the author of The Old, Weird America: The World of Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes (1997), Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads (2005), as well as The Shape of Things to Come: Prophecy and the American Voice (2006), Lipstick Traces (1989), Mystery Train (1975), The Dustbin of History (1995), Dead Elvis (1991), and other books. With Werner Sollors, he is the editor of A New Literary History of America (2009). In recent years he has taught seminars in American Studies at Berkeley and Princeton.

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

- Categories →

- Faculty

- Works

Portfolio

-

Frontiersville

-

Civic Engagement / Luis Jaramillo

-

Elizabeth Gaffney in Conversation with Jessica Sennett

-

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

-

Literature in Evolution / Lena Valencia

-

Transmissions: The Literature of Aids / Josué Rivera

-

Four Poems / Catherine Barnett

-

Christopher Pugh: To Colorado

-

Animal Farm: Timeline & Bias / John Reed

-

She Hath Writ Diligently Her Own Mind: Elizabeth Childers / Bean Haskell

-

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

-

Ari Spool: Bricks

-

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

-

Conrad Hamanaka Yama / Zoe Rivka Panagopoulos & Ricky Tucker

-

Community

-

Class Stories

-

No Scripts / Bean Haskell

-

Spring’s Last Words: Riggio Student Reading / Ashawnta Jackson

-

GPS / Patricia Carlin

-

Midway / Laura Cronk

-

A Certain Rainy Day / Zia Jaffrey

-

The Story Prize

-

The Next Flight / Jefferey Renard Allen

-

The Inquisitive Eater Blog First Year Anniversary: March 18, 2013 / Jessica Sennett

-

Riggio Forum: Sean Howe / Natassja Schiel & Jessica Sennett

-

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

-

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

-

Nonfiction Forum: Tom Lutz / Ashawnta Jackson & Nico Rosario

-

Homage to Bill McKibben / Suzannah Lessard

-

The Unsolved Mystery of “Epitaph to a Love” by Mildred Green, 1948 / Jessica Sennett

-

Dancing About Writing