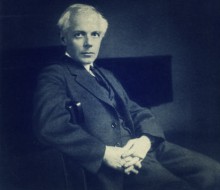

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók

Liben Eabisa

In the Spring 1950 12th Street literary journal published an essay highlighting the last years of composer Béla Bartók. Bartók had moved from Hungary to the United States in the fall of 1940 in protest of an imminent collaboration between his native country and Nazi Germany. He traveled from Budapest to New York with his wife, the pianist Ditta Pasztory, and they came carrying with them only one small bag containing his manuscript for Sonata for 2 Pianos and Percussion. The couple were eventually joined by their son, Peter, who enlisted in the U.S. Navy soon after his arrival in 1942. Bartók, who gained better recognition on this side of the Atlantic posthumously, would spend his final five years here in Manhattan and in Asheville, North Carolina, often struggling with severe illness and shortage of money, but also creating some of his most important works including the masterpiece Concerto for Orchestra.

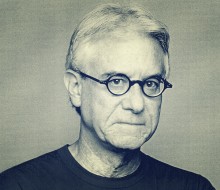

The author of the article, Ed Jablonski, who died in 2004 at the age of 81, graduated from the New School in 1950 and pursued graduate studies at Columbia University in Anthropology. He went on to write several well-known biographies including those of George Gershwin, Harold Arlen, Alan Jay Lerner, and Irving Berlin. According to the New York Times: “At his death he was working on ‘Masters of American Song,’ which his family described as a comprehensive history of American popular music.”

Since Jablonski wrote his piece for 12th Street that launched his successful writing career more than six decades ago, the apartment where Bartók had lived in Midtown at 309 West 57th Street now features a plaque that reads “The Great Hungarian Composer / Béla Bartók / (1881–1945) / Made His Home In This House / During the Last Year of His Life.”

Critics have noted that even though Bartók was financially strapped as mentioned in the profile, the self-exiled composer was not without basic resources. He had been awarded a research fellowship from Columbia University and received support from both admirers of his art as well as rganizations like the American Society of Composers and Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), who assisted him with his medical bills despite not being a member of the association.

Regarding Bartók’s pecuniary difficulties, however, Jablonski points out: “Fiercely proud by nature, Bartók refused payment for anything he felt he did not earn.”

Ed Jablonski’s full article follows below, brought through archives from 12th Street: A Quarterly Volume III 1950 Number 2 to the digital age.

Liben Eabisa is a journalism student at The New School and publishes on the website www.tadias.com.

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

- Categories →

- 12th Street

- Media

- Students

Portfolio

-

Frontiersville

-

Civic Engagement / Luis Jaramillo

-

Elizabeth Gaffney in Conversation with Jessica Sennett

-

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

-

Literature in Evolution / Lena Valencia

-

Transmissions: The Literature of Aids / Josué Rivera

-

Four Poems / Catherine Barnett

-

Christopher Pugh: To Colorado

-

Animal Farm: Timeline & Bias / John Reed

-

She Hath Writ Diligently Her Own Mind: Elizabeth Childers / Bean Haskell

-

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

-

Ari Spool: Bricks

-

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

-

Conrad Hamanaka Yama / Zoe Rivka Panagopoulos & Ricky Tucker

-

Community

-

Class Stories

-

No Scripts / Bean Haskell

-

Spring’s Last Words: Riggio Student Reading / Ashawnta Jackson

-

GPS / Patricia Carlin

-

Midway / Laura Cronk

-

A Certain Rainy Day / Zia Jaffrey

-

The Story Prize

-

The Next Flight / Jefferey Renard Allen

-

The Inquisitive Eater Blog First Year Anniversary: March 18, 2013 / Jessica Sennett

-

Riggio Forum: Sean Howe / Natassja Schiel & Jessica Sennett

-

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

-

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

-

Nonfiction Forum: Tom Lutz / Ashawnta Jackson & Nico Rosario

-

Homage to Bill McKibben / Suzannah Lessard

-

The Unsolved Mystery of “Epitaph to a Love” by Mildred Green, 1948 / Jessica Sennett

-

Dancing About Writing