Down the Manhole

Elizabeth Gaffney

When I was a girl, we sometimes went out on rubbing expeditions. Our target: manhole covers. My mother, a graphic designer and artist and gifted impresario of outings, orchestrated these events, while my father, an artist and college art professor, provided the materials: huge pads of rice paper and various large charcoal sticks and conte crayons that he pilfered from a vast store of supplies ordered for the benefit of his undergraduates. Around this same time, my father was getting involved in a teachers’ union and picketing his own campus in a t-shirt stenciled with a red fist and the word ‘strike.’ He was smoking hashish and painting beautiful, terrifying pictures. He was reading Marvel comics and talking about peace in Southeast Asia. He had long hair and little round glasses and was a member of a coop gallery in SoHo, when SoHo was for art, not shopping. He was too young and maybe not quite cool enough to be a Beatnik, to old by a shade to be a hippie. Or that’s the way I imagine it. Maybe he actually bought the art supplies, or maybe my mother did, but I like to think that he liberated them from the supply closet as compensation in lieu of fair wages.

And then we went out and made imprints of manhole covers all across downtown Brooklyn. Some had writing that identified their function, some just cryptic initials, some beautiful floral or rhythmic graphic elements whose practical purpose was, I presume, to provide pedestrian traction and perhaps even advertising. I have no idea anymore how many such outings took place. There may have been just a few, but their message was fixed in my mind like a Kosmokrete logo in cast iron: Go out and look at the world. Really see it—especially things otherwise likely to go unnoticed. It was about awareness, it was about engagement, it was about making art out of everyday life. The rubbings we made were prominently posted by my mother on the floor-to-ceiling corkboard in her studio, along with an ever-morphing collage of her own designs, drawings, and photographs as well as clippings of interesting typography or graphic design.

These were perfect outings for the child I was: We were mucking around in the dirt, on the street. We were being a bit subversive, it seemed to me, since one member of our expedition often had to stop or redirect traffic. We were making pictures, and miraculously we were doing it entirely without creative anxiety, thanks to the fact that the images were borrowed from the pavement and from the past. Our contribution consisted of noticing them, framing them on our page, and deciding how hard to press.

My parents, as artists, were eager to have their children out discovering beauty and typography and graphic design, and they understood child psychology pretty well. Looking for these things underfoot, where few expected to find anything of value, was just the right kind of fun and worked better than yet another trip to the MoMA. We didn’t have to behave. We were allowed, nay required, to touch. My parents believed that embedding beautiful designs in the asphalt and the sidewalks was a quintessentially democratic, political act. When we went out, we considered not just manhole covers but other items of street furniture, as well: fire hydrants, alarm boxes, street and traffic lights, signage. They were interested in urban renewal and preservation, and so the ideas of street furniture and the livability of the street were important to them. We rated what we saw, and talked about why we did or didn’t like it. To me, the very idea of street furniture was thrilling—it conjured images of nestling in the cushions of imaginary streetcorner sofas and jumping on nonexistent double beds. My mother in particular was also a history buff, and so the connection of the manhole covers to Brooklyn’s past was important. Most of them were old; we tried to figure out exactly how old from the names on them and the wear they had undergone. Some were rubbed so smooth there was nothing to make a rubbing of, and my mind boggled to think of the forces that could scrape such heavy metal down to nothing. When my mother mentioned that the metal wheels of horse-drawn vehicles wore the street down harder that modern rubber tires filled with air, I was catapulted into a new understanding of a previous era. The past had never seemed very believable to me, till then. People might have gone around riding horses and wearing bonnets somewhere out west, say where Little House on the Prairie had transpired, but not on the streets I inhabited. But thanks to manhole covers and several stretches of street still paved with Belgian blocks, not asphalt, also pointed out by my mother, I could suddenly fathom that Brooklyn had been something different once too. History had happened here.

One of the most crucial questions manhole covers raised for me was below the surface. I wanted to go down under them, to find out where they led. It was a little beyond the purview of our outings, however, and I never got further than a few chats with the guys from ConEd or BUG, the local gas company. The workmen generally indulged a young girl’s interest and tolerated a glance down their holes while repair work was going on, but no one ever allowed me to venture down there. To reward our curiosity, my brother and I were given books by our parents about the world beneath the city, some about New York in particular and other, more general ones that covered various types of infrastructure in some depth, including some fairly specific illustrations of how sewage was processed (in those days, not nearly enough). But I was never sated. I never lost the yearning to see for myself what went on beneath the street, and especially my street.

Some years ago, when I began writing a novel set in New York in the 19th century, I found myself unexpectedly setting much of it in the sewers. Of course, not all manholes lead to the sewers: there’s gas, electric, water and nowadays even cable down there as well, but water and sewers were first. I put water aside—too well documented already. Furthermore, I had happened onto a couple of vivid accounts of how bad the city smelled back then, and I decided to follow my nose. The sewers, I found out, were not designed very intelligently, at first. In fact, they were hardly designed at all. It so happened that I was reading mostly about Manhattan’s sewers. Manhattan seemed better documented in general, and I just assumed without thinking much about it that Manhattan and Brooklyn would be in roughly the same boat, sewagewise.

I learned that aside from a few early efforts, such as the one that gave Canal Street its name, most of the city’s early sewers were privately constructed, and there was no master plan until well past mid-century. As a result, the system was not, strictly speaking, a system. The need for sewers in New York greatly increased after the Croton Reservoir project brought upstate water to the metropolis in 1842. The city brought the water to the entire grid of Manhattan. Then, according to their means and their predilections, people brought the water from the mains to their houses for kitchens and bathrooms. But there was no mandate to put in sewer lines at the same time, nor did the city introduce any means for treating the wastewater outflow. Soon, the water table began to rise with very dirty water. Some wealthy people had big sewers hooked up to their homes and businesses, hoping to drain away effluvia swiftly and keep their environments clean, but if their neighbors didn’t or couldn’t do the same, it was to no effect. A clog downstream would impact everyone upstream, regardless of social standing. All manner of pipes and connections were deployed, with an utter lack of awareness of hydrodynamics, making clogs the norm, not the exception. The whole thing was a disaster. Many poor neighborhoods at the edges of the city encompassed low-lying marshes that were plagued with overflows. Fecal-oral spread diseases such as typhoid and cholera were rampant.

And then, while perusing a dissertation on the construction of the New York sewers, I came upon a reference to the excellent sewer system of Brooklyn. I came face to face with a fact I’d known all along, but not thought much about: Brooklyn and Manhattan were separate cities, then, and anything but similar. It turns out that while Manhattan was a cesspool, Brooklyn was not. I looked deeper into the Brooklyn sewers, and the further I went, the prouder I grew. Brooklyn’s sewers were the gold standard of that era, The initial twenty square miles of sewerage was designed in 1857 by Civil War veteran Colonel Julius Walker Adams, who later wrote “Sewers and Drains for Populous Districts,” the 19th century’s definitive textbook on the topic. He studied fluid dynamics, he studied the pros and cons of using water to carry waste through the system, he studied the toxicity of gasses that accumulated in sewers and how to vent them. He even tabulated the volume of excreta produced by cities of various populations, broken down into liquid and solid waste and by gender and age, and specified the size and shape of sewer pipes required to handle it. In Brooklyn he introduced visionary technologies: vitreous clay pipes that let the sewage (and the troublesome flotsam) slide along its route far better than other materials. He created a system that tapered toward its extremities and widened and flowed downhill toward the outlets, to adequately manage the actual volumes flowing through the system at each location. This issue of needing the stuff to flow smoothly away may seem obvious, but it was new, then. No one had worried about bottlenecks overflowing or sludge coming out of suspension to form clogs where water meandered too slowly. The only flaw in Adams’s design was that some of the outlets were below the tide line, which was a problem when storms sent large volumes of water through the conduits, only to find the outlets closed till ebb tide. (It’s a tough one to solve—Brooklyn still struggles with the issue today.) Adams was born in Massachusetts, but he designed Brooklyn’s sewers and remained in charge of them for many years. He was the borough’s own underground genius, and he singlehandedly took the art of sewage management in America forward into the modern era.

The one disappointment for me, in finding out how great Brooklyn’s sewers were, was that I wanted to set my novel in a clogged and fouled sewer system, a place where unfortunate troglodytes were compelled to haul the muck away in buckets, where methane explosions might rock the tunnels and putrid gasses threatened lives. It meant that I ended up focusing far more on Manhattan in my novel that I, as a loyal Brooklynite, otherwise would have. Brooklyn’s sewers were just too good to be really interesting. I came across some fascinating Brooklyn sewer disasters just a little later than my period—the borough expanded swiftly, doubling in size from 1860 to 1870, necessitating plenty of new construction. I could have written an entire novel about the following headline from The New York Times, in November of 1908 (and I still may): “BROOKLYN EXPLOSION ENGULFS A SCORE—Men, Women, and Children go down under Flood, Fire, and Earth in Gold Street Sewer. Victims buried under tons of debris fifty feet down, while many slide into death pit.” The excavation for the thirteen-and-a-half-foot-diameter trunk sewer was about fifty feet deep and thirty feet in width. Either a collapse of the trench ruptured a gas main, or an independently occurring gas leak was ignited by a spark in the excavation work. It was never determined for sure. There was a list of names, ages and home addresses of the victims, including a group of six and seven year olds: Clarice Brady, Vincent Doherty, John O’Grady and William Dalton, who lived in two adjacent buildings near the disaster. I can picture them out together, a little gang adventurously exploring the margins of the work site just before it blew, the same way I would have, at their age. Sixty off-duty telephone operators were called in to contact some 10,000 customers of the local gas company, to urge them to turn off all gas cocks, lest further fires and poisoning ensue after service was restored. The fact that the Borough Inspector of Sewers was there right when the disaster happened and died with the rest of his workers opens up the possibility of a promising plotline rife with political scandal and intrigue. Maybe I’ll write it one day, but when I came across the incident, I was already committed to a story set at the time of the Brooklyn Bridge’s construction, so I let the 1908 explosion go. I focused instead on the expansion of Manhattan’s dysfunctional tunnels in the post-Civil War period. It was good fun, finding out which of Manhattan’s streets had tunnels with a large enough bore to let a gangster crawl through them. Still, I wished there was some way to bring my sewer research home, to Brooklyn. Even after I’d finished my novel, I wanted to go down there.

I’ve tried to get down into the sewers on and off for years, but it’s not so easy. There was a time that the city offered a mini-training session on entering confined spaces and took curious professionals with half-decent excuses on tours. I’ve seen documentaries and pretty much every piece of film footage ever shot under New York, but I still haven’t seen my dark, damp Mecca with my own eyes. I came around too late to be granted access as a layperson. Even writers who’ve covered the topic for news outlets have had a hard time getting access, since 9/11. For me, a mere novelist interested in history, legal entry has proven impossible, so far. Instead, I’ve had to make do with Paris, where the highlight of a romantic getaway weekend for me and my husband a couple years back was a tour of the Musee d’Egout—an institution after my own heart, not just dedicated to but located in the sewers. All right, it wasn’t exactly the highlight of my husband’s itinerary, but he consented to go along. I marveled at the exhibits detailing the evolution of flow management and sludge decomposition through the centuries and exclaimed at the fresh and unsewerlike whiff of the effluent rushing beneath our feet and gathering in fog banks in the cool tunnels. He groaned and registered his eagerness to go back aboveground and wash his hands as soon as possible, then go sit in a cafe.

Now we have a daughter of our own who has lately begun putting sentences together, telling stories, and scribbling with markers and crayons. Before I know it, it will be time for me to spearhead some fabulous and inspiring art expeditions. I look forward to teaching her all about the city she lives in and showing her that an urban childhood can be as much of an idyl as the clichéd suburban one. It’s important to me that she grow up in a diverse community, and I’ll enjoy making sure she’s aware of the infrastructure that enables us all to live in such splendid density: the buildings, the roads, the trains, the tunnels. I’m still proud of Brooklyn’s sewers for having been among the best in the world, once, but I’m sorry to say I won’t be able to brag about our borough’s sewers to my daughter. Like that of many old big cities, New York City’s combined wastewater system is badly outmoded. The ideal system has one set of pipes for wastewater from toilets and drains, which gets treated, and a second one for storm runoff. The trouble with doing it the old way, as we do here, is that whenever it rains, even just a little, the volume flowing through the pipes overwhelms the treatment plants and raw sewage shoots into the harbor, causing health and environmental problems.

Maybe it’s a parent’s fear of pathogens that might harm her child, or just the fact that I’ve changed so many diapers in the past couple years, but as for me, I don’t hear the Siren song of the sewer tunnels so acutely these days. I love Brooklyn’s beauty more now,and generally choose parks and gardens and bridges over the crime and the guts. When, I eventually take my own daughter out to the streets to make manhole cover rubbings. I expect I’ll emphasize the design element, just as my parents did, rather than the places where the tunnels beneath them lead. If Lucy should decide to follow her own nose down into the underworld, I’d be thrilled. She’s a ballsy little girl, and I can imagine her going where I never did . Maybe she’ll even bring me along. But till then, I’ll be content to enjoy the city’s grandest sewers the way they were designed to be used: from a healthy distance.

Read Elizabeth Gaffney’s reflection on The Riggio Honors Program: Writing & Democracy, and watch an interview with her.

Elizabeth Gaffney is the author of the novel Metropolis, which was a Barnes and Noble Discover Great New Writers selection. She has translated three books from German and her stories have appeared in many literary magazines. She worked as a staff editor at George Plimpton’s Paris Review and currently is editor at large of the literary magazine A Public Space. Gaffney has been a resident artist at Yaddo, the MacDowell Colony and the Blue Mountain Center.

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

- Categories →

- Faculty

- Works

Portfolio

-

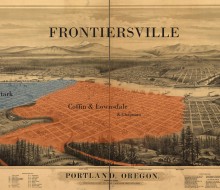

Frontiersville

-

Civic Engagement / Luis Jaramillo

-

Elizabeth Gaffney in Conversation with Jessica Sennett

-

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

-

Literature in Evolution / Lena Valencia

-

Transmissions: The Literature of Aids / Josué Rivera

-

Four Poems / Catherine Barnett

-

Christopher Pugh: To Colorado

-

Animal Farm: Timeline & Bias / John Reed

-

She Hath Writ Diligently Her Own Mind: Elizabeth Childers / Bean Haskell

-

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

-

Ari Spool: Bricks

-

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

-

Conrad Hamanaka Yama / Zoe Rivka Panagopoulos & Ricky Tucker

-

Community

-

Class Stories

-

No Scripts / Bean Haskell

-

Spring’s Last Words: Riggio Student Reading / Ashawnta Jackson

-

GPS / Patricia Carlin

-

Midway / Laura Cronk

-

A Certain Rainy Day / Zia Jaffrey

-

The Story Prize

-

The Next Flight / Jefferey Renard Allen

-

The Inquisitive Eater Blog First Year Anniversary: March 18, 2013 / Jessica Sennett

-

Riggio Forum: Sean Howe / Natassja Schiel & Jessica Sennett

-

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

-

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

-

Nonfiction Forum: Tom Lutz / Ashawnta Jackson & Nico Rosario

-

Homage to Bill McKibben / Suzannah Lessard

-

The Unsolved Mystery of “Epitaph to a Love” by Mildred Green, 1948 / Jessica Sennett

-

Dancing About Writing