BOB DYLAN’S MEMORY PALACE

Robert Polito

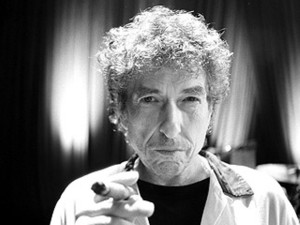

You could call them “covers,” these invocations of poems and novels that Dylan slips into his songs on recent recordings, and the collections are effortlessly retitled: Bob Dylan Sings the Exile Poems of Publius Ovividius Naso, Henry Timrod Revisited, Ovid on Ovid, Live from the Black Sea, and From Twain to Fitzgerald: Nobody Sings Studies in Classic American Literature Better Than Dylan.

You might also say they are performed “under cover,” as all this escalating literary traffic tends to fall among Dylan’s many covert operations. Poems and novels infiltrate his songs mostly through the camouflage of more flagrant smuggling. In “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” or “Nettie Moore,” or “Summer Days” it’s Muddy Waters, “Gentle Nettie Moore,” and Charlie Patton you register first, and then only later, if at all, Ovid, Timrod, and The Great Gatsby. Dylan’s literary stealth tilts toward the second story: a bygone Timrod rather than a celebrated Poe, Whitman, or Dickinson; Ovid’s obscurer Tristia over his Metamorphoses. So that when during “Thunder on the Mountain,” the lead-in track to Modern Times, Dylan sings, “I’ve been sitting down studying The Art of Love / I think it will fit me like a glove,” that glove is calculated to point at Ovid while also covering up the significant fingerprints here. Of the perhaps 20 nods to the Roman poet across the songs that follow none (as far as I can tell) will touch The Art of Love, the Ovidian sleight-of-hand inside Modern Times emanating instead from Tristia, Black Sea Letters, The Amores, and his “Cures for Love.”

You might also say they are performed “under cover,” as all this escalating literary traffic tends to fall among Dylan’s many covert operations. Poems and novels infiltrate his songs mostly through the camouflage of more flagrant smuggling. In “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” or “Nettie Moore,” or “Summer Days” it’s Muddy Waters, “Gentle Nettie Moore,” and Charlie Patton you register first, and then only later, if at all, Ovid, Timrod, and The Great Gatsby. Dylan’s literary stealth tilts toward the second story: a bygone Timrod rather than a celebrated Poe, Whitman, or Dickinson; Ovid’s obscurer Tristia over his Metamorphoses. So that when during “Thunder on the Mountain,” the lead-in track to Modern Times, Dylan sings, “I’ve been sitting down studying The Art of Love / I think it will fit me like a glove,” that glove is calculated to point at Ovid while also covering up the significant fingerprints here. Of the perhaps 20 nods to the Roman poet across the songs that follow none (as far as I can tell) will touch The Art of Love, the Ovidian sleight-of-hand inside Modern Times emanating instead from Tristia, Black Sea Letters, The Amores, and his “Cures for Love.”

Poems, novels, films, and songs, whatever else they do, direct a conversation with the great dead, and Dylan’s ghostwriting on his last three CDs, Time Out of Mind, “Love and Theft,” and Modern Times is the most far-reaching of his career. Late in the 16th century, historian Jonathan Spence recounts, the Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci “taught the Chinese how to build a memory palace. He told them that the size of the palace would depend on how much they wanted to remember . . . One could create modest palaces, or one could build less dramatic structures such as a temple compound, a cluster of government offices, a public hostel, or a merchants’ meeting lodge. If one wished to begin on a still smaller scale, then one could erect a simple reception hall, a pavilion, or a studio . . . In summarizing this memory system, he explained that these palaces, pavilions, divans were mental structures to be kept in one’s head, not solid objects to be literally constructed out of ‘real’ materials . . . To everything we wish to remember, wrote Ricci, we should give an image; and to every one of these images we should assign a position where it can repose peacefully until we are ready to reclaim it by an act of memory.” [1]

On Modern Times, “Love and Theft,” and Time Out of Mind, Dylan is teaching us how to build a memory palace, “mental structures”—in this instance, songs—that will lodge past and present, the living and the dead. In Chronicles Volume I, his prose investigation of artistic self-invention and re-invention, he concluded his account of going inside the New York Public Library to read contemporary newspaper reportage on the Civil War with a spatial image for his memory that shrinks Ricci’s elate palace to a roadside storage unit. “I crammed my head full of as much of this stuff as I could stand and locked it away in my mind out of sight, left it alone,” Dylan writes. “Figured I could send a truck back for it later.” [2]

Echoing Aquinas, Augustine, and Ignatius of Loyola, Ricci stressed that the memory palace must not be envisioned as a passive repository, but by “incorporate[ing] these ‘memories’ of an unlived past into the spiritual present”[3] his mnemonic system was an instrument for spiritual practice with ancient links to alchemy, magic, and writing. “As for those worthy figures who lived a hundred generations ago,” Ricci argued, “although they too are gone, yet thanks to the books they left behind we who come after can hear their modes of discourse, observe their grand demeanor, and understand both the good order and the chaos of their times, exactly as if we were living among them.”[4] Or, as Dylan sings in “Rollin’ and Tumblin’”:

Well, the night’s filled with shadows, the years are filled with early doom

The night is filled with shadows, the years are filled with early doom

I’ve been conjuring up all these long dead souls from their crumblin’ tombs

Making the dead available to the living, the memory palace proposes a mechanism for rendering all time—past, present, future—modern times. Since in this little verse of “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” the opening repeated phrases derive from “Our Willie,” an 1865 poem by Timrod, and the final line comes from Ovid’s poem of c. 16 BCE The Amores, and both are cut inside a blues out of Hambone Willie Newbern and Muddy Waters, Dylan manages at once here to describe and embody that mechanism.

*

As a culture we appear to have forgotten how to experience works of art, or at least how to talk about them plausibly or smartly. A latest instance was the “controversy” in the fall of 2006 shadowing Dylan’s recurrent adaptation of phrases from poems by Henry Timrod, a nearly vanished 19th century American poet, essayist, and Civil War newspaper correspondent, for Modern Times. That our most gifted and ambitious songwriter would revive Timrod on a No. 1 best-selling CD across America, Europe, and Australia might prompt a lively concatenation of responses ranging from “Huh? Henry Timrod? Isn’t that interesting . . .” to “Why?” But narrowing the Dylan/Timrod phenomenon (see the New York Times article “Who’s This Guy Dylan Who’s Borrowing Lines From Henry Timrod?” and a subsequent op ed piece “The Ballad of Henry Timrod” by singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega) into possible plagiarism is to confuse, well, art with a term paper. [5]

Timrod was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1828, his arrival in this world falling two years after Stephen Foster and two years before Emily Dickinson. His work, too, might be styled as falling between theirs: sometimes dark and skeptical, other times mawkish, old-fashioned. These are passages from five Timrod poems Dylan recast for “When the Deal Goes Down”:

From “Retirement”:

There is a wisdom that grows up in strife,

And one—I like it best—that that sits at home

And learns its lessons of a thoughtful ease.

From a sonnet, “I thank you, kind and best beloved friend”:

If I, indeed, divine their meaning truly,

And not unto myself ascribe, unduly,

Things which you neither meant nor wished to say,

Oh! Tell me, is the hope then all misplaced?

From “Two Portraits”:

Still stealing on with pace so slow

Yourself will scarcely feel the glow . . .

From “A Rhapsody of a Southern Winter Night”:

These happy stars, and yonder setting moon,

Have seen me speed, unreckoned and untasked,

A round of precious hours.

Oh! here, where in that summer noon I basked,

And strove, with logic frailer than the flowers,

To justify a life of sensuous rest,

A question dear as home or heaven was asked,

And without language answered. I was blest!

From “A Vision of Poesy”:

. . . and at times

A strange far look would come into his eyes,

As if he saw a vision in the skies. [6]

Dylan, I’m guessing, is fascinated by both aspects of Timrod, the antique alongside the brooding. Often tagged the “laureate of the Confederacy”—a title apparently conferred upon him by none other than Tennyson—he still shows up in anthologies because of poems he wrote celebrating and then mourning the new Southern nation, particularly “Ethnogenesis” and “Ode Sung on the Occasion of Decorating the Graves of the Confederate Dead at Magnolia Cemetery.” Early on, Whittier and Longfellow admired Timrod, and his “Ode” stands behind Allen Tate’s “Ode to the Confederate Dead” (and thus in turn behind Robert Lowell’s “For the Union Dead”).

On Modern Times Dylan shuns anthology favorites, but his album focuses at least 13 instances of phrases spread across five songs—“Spirit on the Water,” “Workingman’s Blues #2,” “Beyond the Horizon,” “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” and “When the Deal Goes Down”—culled from as many as eight Timrod poems, mostly poems about love, friendship, loss, death, and poetry. (Note: “Katie” and “To Thee,” besides the six Timrod poems already noted.) Dylan quoted Timrod’s “Charleston” in “’Cross the Green Mountain,” a song he contributed to the soundtrack of the 2003 Civil War film Gods and Generals. Two years earlier he glanced at “Vision of Poesy” for “Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum” on “Love and Theft.”

On Modern Times Dylan shuns anthology favorites, but his album focuses at least 13 instances of phrases spread across five songs—“Spirit on the Water,” “Workingman’s Blues #2,” “Beyond the Horizon,” “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” and “When the Deal Goes Down”—culled from as many as eight Timrod poems, mostly poems about love, friendship, loss, death, and poetry. (Note: “Katie” and “To Thee,” besides the six Timrod poems already noted.) Dylan quoted Timrod’s “Charleston” in “’Cross the Green Mountain,” a song he contributed to the soundtrack of the 2003 Civil War film Gods and Generals. Two years earlier he glanced at “Vision of Poesy” for “Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum” on “Love and Theft.”

For “Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum,” Dylan cribbed those “stately trees” and “secrets of the breeze” from Timrod’s “A Vision of Poesy,” as well as the epigrammatic, “A childish dream is a deathless need,” and the ensuing rhyme of “need” and “creed.” On Modern Times Timrod accents texture, tone, and atmosphere. For “Spirit on the Water,” Dylan found “explain / The sources of this hidden pain” in “Two Portraits.” For “Workingman’s Blues #2” he located “to feed my soul with thought” in “To Thee,” and that rhyming “lover’s breath” and “a temporary death” also in “Two Portraits.” “Beyond the Horizon” teases out at least four Timrod poems—“In the long hours of twilight” arriving via “A Vision of Poesy”; “mortal bliss” from “Our Willie”; “an angel’s kiss” from “A Rhapsody of a Southern Winter Night”; and those chiming “bells of St. Mary” from “Katie.” Dylan often absorbs Timrod by reversing or otherwise varying the original sense—“But not to feed my soul with thought,” Timrod wrote; and sleeping “virtues” rather than sleep itself intersected “a temporary death.”[7] “I always try to turn a song on its head,” Dylan told Robert Hilburn in a 2004 interview about songwriting. “Otherwise, I figure I’m wasting the listener’s time.” [8]

The pining strains of Timrod’s inflections notably complement the ‘20s, ‘30s, and ‘40s popular singers Dylan steadily evokes on Modern Times, such as Bing Crosby, who presumably too is acknowledged here, also via that reference to The Bells of St. Mary’s. Perhaps more surprisingly, Timrod does not (as far as I can tell) grace “Nettie Moore,” Dylan’s revisiting of “Gentle Nettie Moore” (aka “The Little White Cottage”), a minstrelsy song about a young girl sold into slavery published by Marshall S. Pike and James S. Pierpont in 1857.

*

But Henry Timrod, I want to suggest, might only inscribe another deep-cover Dylan covert operation, a deflective gesture intended to divert our scrutiny from the actual priority of Ovid on Modern Times. During his sophomore year at Hibbing High School Robert Zimmerman joined the Latin Club, and once recognized, Ovid is everywhere, Tristia, Black Sea Letters, “Cures for Love,” and The Amores, all in translations by Peter Green: the early love poems, certainly, but especially the poems Ovid wrote after he was exiled by Augustus to Tomis, on the shores of the Black Sea, perhaps because of his scandalous verses, perhaps because of still-enigmatic offenses against the Empire.[9] From “Spirit on the Water,” “Rollin’ and Tumblin’,” and “Someday Baby” through “Workingman’s Blues #2,” “Nettie Moore,” “The Levee’s Gonna Break,” and “Ain’t Talkin’,” at least seven of the ten songs refocus language, often entire lines from Green’s Ovid, and the Ovidian netting emerges as more ubiquitous than any of the Dylan websites have so far indicated.[10] Amid variations for his own metrical designs, Dylan pirates locutions no songwriter would need to steal from a Latin poet, since they sound like they already spring from old blues, country, and rockabilly lyrics—“a face that begs for love,” “am I wrong in thinking / That you have forgotten me,” “I swear I ain’t gonna touch another one for years,” “dearer to me than myself, as you yourself can see,” “you got me so hooked,” and “I want to be with you any way I can.” [11]

During the anatomy of his reading in Chronicles, Dylan recalls that on the shelves of Ray Gooch’s New York library, “Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the scary horror tale, was next to the autobiography of Davy Crockett.”[12] Here, classical mythology jostles American legend. Publius Ovidius Naso was born into a landed-gentry family at Sulmo (now Sulmona) in central Italy in 43 B.C. As Green observes for his introduction to The Poems of Exile, this was “the year after Caesar’s assassination” and Ovid “grew up during the violent death throes of the Roman Republic.”[13] Ovid published a version of The Amores as early as 15 B.C., soon followed by Heroides, The Art of Love, Remedia Amoris, Metamorphoses, and Fasti. Augustus exiled him to Tomis (now Constanta) in A.D. 8. “It was two offenses undid me,” Ovid alleged in Tristia, “a poem and an error: / on the second, my lips are sealed.”[14] One genealogical angle on the Dylan/Ovid connection is that in Chronicles he traces his own family back to the cities and towns along the Black Sea. “My grandmother’s voice possessed a haunting accent,” he reports, “face always set in a half‑despairing expression. . . . Originally, she’d come from Turkey, sailed from Trabzon, a port town across the Black Sea.” He links Odessa—the city his grandmother traveled from to America—to Duluth: “the same kind of temperament, climate and landscape and right on the edge of a big body of water.”[15]

During the anatomy of his reading in Chronicles, Dylan recalls that on the shelves of Ray Gooch’s New York library, “Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the scary horror tale, was next to the autobiography of Davy Crockett.”[12] Here, classical mythology jostles American legend. Publius Ovidius Naso was born into a landed-gentry family at Sulmo (now Sulmona) in central Italy in 43 B.C. As Green observes for his introduction to The Poems of Exile, this was “the year after Caesar’s assassination” and Ovid “grew up during the violent death throes of the Roman Republic.”[13] Ovid published a version of The Amores as early as 15 B.C., soon followed by Heroides, The Art of Love, Remedia Amoris, Metamorphoses, and Fasti. Augustus exiled him to Tomis (now Constanta) in A.D. 8. “It was two offenses undid me,” Ovid alleged in Tristia, “a poem and an error: / on the second, my lips are sealed.”[14] One genealogical angle on the Dylan/Ovid connection is that in Chronicles he traces his own family back to the cities and towns along the Black Sea. “My grandmother’s voice possessed a haunting accent,” he reports, “face always set in a half‑despairing expression. . . . Originally, she’d come from Turkey, sailed from Trabzon, a port town across the Black Sea.” He links Odessa—the city his grandmother traveled from to America—to Duluth: “the same kind of temperament, climate and landscape and right on the edge of a big body of water.”[15]

I’m guessing that Green’s translations appeal to Dylan because Green himself is so mercurial a verbal trickster, and there are moments when Ovid even appears to be channeling early Dylan. “You better think twice,” Green has Ovid advising on the same page of The Amores where Dylan would have discovered, “Catch your opponents sleeping / And unarmed. Just slaughter them where they lie.” [16]

Ovid is talking about lovers and bedroom maneuvers here, and much as Timrod, he insinuates ambiance, timber, and character across Modern Times. Along with those “crumbling tombs” for “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” (or as Green blues-ily translates Ovid: “She conjures up long-dead souls from their crumbling sepulchres / And has incantations to split the solid earth.”), Dylan plucked that “house-boy” and “well-trained maid” from The Amores, albeit in a neat inversion. Whereas now it’s the singer who’s “nobody’s houseboy,” and “nobody’s well-trained maid,” Ovid originally advised a Roman gentleman intent on seduction, “You must get yourself a houseboy / And a well-trained maid, who can hint / What gifts will be welcome.” An ostensibly Katrina-esque detail from “The Levee’s Gonna Break”—“Some people got barely enough skin to cover their bones”—first appeared in Tristia amidst Ovid’s description of his own harsh life in Tomis, after his exile from Rome. For “Someday Baby” Dylan gleaned “I’m gonna drive you from your home just like I was driven from mine” from a contrast Ovid posed between his own fate on the Black Sea and the journey of Odysseus: “He was making for his homeland / A cheerful victor: I was driven from mine, / fugitive, exile, victim.” [17]

Ovid is talking about lovers and bedroom maneuvers here, and much as Timrod, he insinuates ambiance, timber, and character across Modern Times. Along with those “crumbling tombs” for “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” (or as Green blues-ily translates Ovid: “She conjures up long-dead souls from their crumbling sepulchres / And has incantations to split the solid earth.”), Dylan plucked that “house-boy” and “well-trained maid” from The Amores, albeit in a neat inversion. Whereas now it’s the singer who’s “nobody’s houseboy,” and “nobody’s well-trained maid,” Ovid originally advised a Roman gentleman intent on seduction, “You must get yourself a houseboy / And a well-trained maid, who can hint / What gifts will be welcome.” An ostensibly Katrina-esque detail from “The Levee’s Gonna Break”—“Some people got barely enough skin to cover their bones”—first appeared in Tristia amidst Ovid’s description of his own harsh life in Tomis, after his exile from Rome. For “Someday Baby” Dylan gleaned “I’m gonna drive you from your home just like I was driven from mine” from a contrast Ovid posed between his own fate on the Black Sea and the journey of Odysseus: “He was making for his homeland / A cheerful victor: I was driven from mine, / fugitive, exile, victim.” [17]

Yet Ovid, unlike Timrod, also furnished essential structural scaffolding for songs on Modern Times, yielding transitions and key images. The strongest songs are all but unthinkable without Ovid, at least Green’s Ovid. The devastating final tag of the chorus for “Nettie Moore”—“The world has gone black before my eyes”—issues from a dream vision in The Amores. Beyond the bluesy phrases already noted, a partial inventory for “Workingman’s Blues #2” tracks “My cruel weapons have been put on the shelf,” “No one can ever claim / That I took up arms against you,” and “I’m all alone and I’m expecting you / To lead me off in a cheerful dance” back to Tristia.[18] Ovid loops through “Ain’t Talking” as insistently as the “Heart’s burning, still yearning” refrain Dylan imported from the Stanley Brothers:

If I catch my opponents ever sleeping,

I’ll just slaughter them where the lie.

They will tear your mind away from contemplation

All my loyal and my much-loved companions

They approve of me and share my code

Make the most of one last extra hour

I practice a faith that’s long-abandoned

Who says I can’t get heavenly aid?

The suffering is unending

Every nook and cranny has its tears.

I’m not nursing any superfluous fears

In the last outback at the world’s end[19]

Each of these vitalizing lines, again calibrated by elisions and reversals, arise from Tristia, The Amores, and Black Sea Letters. Ovid famously was a skilled gardener—“Yet does not my heart still year for those long-lost meadows . . . those gardens set amid pine-clad hills,” as he wrote in the first of The Black Sea Letters. So pervasive is his imprint on “Ain’t Talkng” that it’s tempting to set the song in the abandoned gardens of his country villa. “There’s no one here,” Dylan sings, “the gardener is gone.”[20]

*

From the dustup in the Times—after our paper of record found a middle school teacher who branded Dylan “duplicitous,” Suzanne Vega earnestly supposed that Dylan probably hadn’t filched the texts “on purpose”—you might not know we just lived through a century of Modernism. For Timrod and Ovid are just the tantalizing threshold into Dylan’s vast memory palace of echoes. Besides Ovid and Timrod, for instance, Modern Times taps into the Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Samuel, John, Luke, among others), Tennyson, Robert Johnson, Memphis Minnie, Kokomo Arnold, Muddy Waters, Sonny Boy Williamson, Blind Lemon Jefferson, the Stanley Brothers, Merle Haggard, Hoagy Carmichael, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, standards popularized by Jeanette MacDonald, Crosby, and Frank Sinatra, as well as vintage folk songs like “Wild Mountain Thyme,” or “Frankie and Albert.”

Still more astonishing, though, his prior two recordings Time Out of Mind and “Love and Theft” could be described as rearranging the entire American musical and literary landscape of the past 150 years, except the sources he adapts aren’t always American or so recent. Please forgive another Homeric catalogue, but the scale and range of Dylan’s allusive textures are vital to an appreciation of what he’s after on his recent recordings. On Time Out of Mind and “Love and Theft” he refracts folk, blues, and pop songs created by or associated with Crosby, Sinatra, Charlie Patton, Woody Guthrie, Blind Willie McTell, Doc Boggs, Leroy Carr, Bessie Smith, Billie Holiday, Elvis Presley, Blind Willie Johnson, Big Joe Turner, Wilbert Harrison, the Carter Family, and Gene Austin, alongside anonymous traditional tunes and nursery rhymes. But the revelation involves the cavalcade of film and literature fragments: W. C. Fields, the Marx Brothers, assorted film noirs, As You Like It, Othello, Robert Burns, Lewis Carroll, Huckleberry Finn, The Aeneid, The Great Gatsby, Junichi Saga’s Confessions of a Yakuza, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, and Wise Blood. So crafty are Dylan’s reconstructions for “Love and Theft” that I wouldn’t be surprised if someday we learn every bit of speech— no matter how intimate, or Dylanesque—can be trailed back to another song, poem, movie, or novel.

One conventional approach to Dylan’s songwriting references “folk process” and recognizes that he’s always operated as a magpie, recovering and transforming hand-me-down materials, lyrics, tunes, even film dialogue (notably on his 1985 album Empire Burlesque). Folk process can readily map the associations linking “It Ain’t Me Babe” and “Go ‘Way from My Window,” or tail his variations on traditional blues triplets on “Rollin’ and Tumblin’.” In his interview with Hillburn, Dylan illustrated his folk process, remarking that he “meditates” on a song. “I’ll be playing Bob Nolan’s ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds,’ for instance, in my head constantly—while I’m driving a car or talking to a person or sitting around or whatever. People will think they are talking to me and I’m talking back, but I’m not. I’m listening to the song in my head. At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.” [21]

Yet what about Ovid and Timrod, or Twain, Fitzgerald, O’ Connor, and Confessions of a Yakuza? It’s no stretch to imagine a writer rehearsing Timrod’s “A childish dream is now a deathless need,” or Ovid’s “I’m in the last outback at the world’s end,” on the way to a song. But the lyrics that draw on multiple Ovid and Timrod poems, and shrewdly tweak the sources? That play Ovid against Timrod, or merge the two into a single verse? Might that require books, notes, other constellations of intention? Perhaps along the lines of what Dylan said of painter Norman Raeben and Blood on the Tracks—“He put my mind and my hand and my eye together, in a way that . . . did consciously what I used to do unconsciously”?[22] Folk process probably validates Dylan in his current designs, but if those allusive gestures are also folk process, then a folk process pursued with such intensity, scope, audacity, and verve eventually explodes into Modernism. Dylan seems galvanized by the ways folk process bumps up against Modernism, and the practices of the great blues songwriters intersect the inter-textual dispositions of the Classical poets. As far back as “Desolation Row,” he sang of “Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot / Fighting in the captain’s tower / While calypso singers laugh at them / And fishermen hold flowers.” His emphatic nods to the past on Time Out Of Mind, “Love and Theft” and Modern Times probably can best be apprehended as instances of Modernist collage.

If we think of Modernist collages as verbal echo chambers of harmonizing and clashing reverberations, then they tend to organize into two types. Those collaged texts, like Pound’s Cantos or Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” where we are meant to remark the discrepant tones and idioms of the original texts bumping up against one other; and those collaged texts, composed by poets as various as Kenneth Fearing, Lorine Niedecker, Frank Bidart, and John Ashbery, that aim for an apparently seamless surface. A model of the former is the ending to “The Waste Land”:

London Bridge is falling down falling down falling down

Poi s’ascose nel foco che gli affina

Quando fiam ceu chelidon—O swallow swallow

Le Prince d’Aquitaine à la tour abolie

These fragments I have shored against my ruins

Why then Ile fit you. Hieronymo’s mad againe.

Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata.

Shantih shantih shantih [23]

The following passage by Frank Bidart, from his poem “The Second Hour of the Night,” proves as allusive as Eliot’s, nearly every line rearranging elements assembled not only from Ovid, his main source for the Myrrha story, but also Plotinus and even Eliot. But instead of incessant fragmentation, we experience narrative sweep and urgency:

As Myrrha is drawn down the dark corridor toward her father

not free not to desire

what draws her forward is neither COMPULSION nor FREEWILL:—

or at least freedom, here choice, is not to be

imagined as action upon

preference: no creature is free to choose what

allows it its most powerful, and most secret, release:

I fulfill it, because I contain it—

it prevails, because it is within me—

it is a heavy burden, setting up longing to enter that

realm to which I am called from within . . .

As Myrrha is drawn down the dark corridor toward her father

not free not to choose

she thinks, To each soul its hour.[24]

Dylan’s songwriting inclines toward the cagier, deflected Bidart-Ashbery-Fearing-Neidecker Modernist mode. We would scarcely realize we are inside a collage unless someone told us, or we abruptly seized on a familiar locution. The wonder of the dozen or so nuggets Dylan sifted from Confessions of a Yakuza for “Love and Theft” is how casual and personal they sound dropped into his songs, a sentence once about a bookmaker reemerging as an aside on marriage in “Floater”: “A good bookie makes all the difference in a gambling joint—it’s up to him whether a session comes alive or falls flat.”[25] Not one of those “Love and Theft” songs, of course, is remotely about a Yakuza, or gangster of any persuasion.

The issue of what we gain if we heed the multifarious allusions lodges a more tangled crux. For a long time I preferred to think of the phrases as curios of vernacular speech picked up from Dylan’s listening or reading that slant his songs into something like collective, as against individual utterances, and only locally influence his designs. But after immersion in Ovid and Timrod, it’s hard to miss both grand and specific calculations. Dylan manifestly is, for instance, fixated on the American Civil War. “The age that I was living in didn’t resemble this age,” as he wrote in Chronicles, “but it did in some mysterious and traditional way. Not just a little bit, but a lot. There was a broad spectrum and commonwealth that I was living upon, and the basic psychology of that life was every bit a part of it. If you turned the light towards it, you could see the full complexity of human nature. Back there, America was put on the cross, died, and was resurrected. There was nothing synthetic about it. The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything I would write.” [26]

His 2003 film Masked & Anonymous takes place against the backdrop of another interminable domestic war during an unspecified future. Dylan sees links between the Civil War and America now—the echoes from Timrod help him frame and sustain those links. Ovid too lived through the assassination of Julius Caesar, the violent Roman internal conflicts, and wrote at the start of the Pax Augusta. Even the tibits of Yakusa oral history irradiate the terrain. On recordings steeped in empire, war, corruption, masks, moral failure, male power, and self-delusion, aren’t Tokyo racketeers as apt as Charlie Patton or the Carter family? Ovid and Timrod (or Twain, O’Connor, and Fitzgerald) should not be mistaken for a high-brow alternative to the “old weird America” of Dock Boggs; they’re an extension of it.

Exile, ghosts, romantic and spiritual abandonment, wary dawn departures, an abiding death-in-life—the devastated inflections of Tristia and Black Sea Letters offer the closest analogue in poetry I know to Time Out of Mind, particularly to “Love Sick,” “Not Dark Yet,” “Tryin’ to Get to Heaven,” and “Highlands.” Ovid obsessively revisits his apprehension that he “made a few bad turns”:

. . . yet sick though my body is, my mind is sicker

from endless contemplation of its woes.

Absent the city scene, absent my dear companions,

absent (none closer to my heart) my wife:

what’s here is a Scythian rabble, a mob of trousered Getae—

troubles seen and unseen both prey on my mind.

One hope alone in all this brings me some consolation—

that my troubles may be soon cut short by death. [27]

The phantoms of Ovid and Timrod transform individual songs. Dylan’s “Rollin’ and Tumblin’” pushes past the eroticism—and erotic anger—of the Hambone Willie Newbern and Muddy Waters versions towards something like forgiveness: “Let’s forgive each other, darlin’, let’s go down to the Greenwood Glen.” The axle of that forgiveness is the sudden nod to mortality in the verse I quoted earlier about the “long dead souls” and their “crumbling tombs,” out of Ovid. Yet isn’t our alertness to mortality also deepened after we know that the prior repeated line that Dylan reshaped from Timrod, “Well, the night is filled with shadows, the years are filled with early doom,” draws on “Our Willie,” a heart-sore, self-accusing poem about the death of the poet’s son?[28] Similarly, isn’t the haunted and inconsolable refrain from “Nettie Moore”—“the world has gone black before my eyes”—still more haunted and inconsolable after we return the line to Ovid’s nightmare vision about “the stain of adultery” in The Amores? In “Workingman’s Blues #2” Dylan persistently roots his litany of the troubles of globalization in references to Ovid’s exile from Rome, as though the poet (and his poems) were only the first victims of outsourcing among the “proletariat.” “Ain’t Talkin’,” as submitted earlier, all but namechecks Ovid’s dark, bitter personal story, reclaiming his grief and anger, his vengeance and narratives of a “world gone wrong” as Dylan’s own.

When Dylan lifts from Ovid and Timrod, the phrases often occur during passages where the original poets discuss their art. That “cheerful dance” and those “countless foes” are items in Ovid’s reply to a friend who urged him to “divert these mournful days with writing.”[29] As Dylan sings, “I practice a faith that’s long abandoned,” he glances at a section of Tristia where Ovid is reflecting on the quandaries of keeping his Latin alive amidst the “barbaric” languages of Tomis:

Yet, to prevent my voice being muted

in my native speech, lest I lose the common use

of the Latin tongue, I converse with myself, I practice

terms long abandoned, retrace my sullen art’s

ill-fated sins. Thus I drag out my life and time, thus

tear my mind from the contemplation of my woes.

Through writing I seek an anodyne to misery: if my studies

Win me such a reward, that is enough. [30]

Even when Ovid exclaimed, “I want to be with you any way I can,” he was not addressing a lover but his audience back in Rome reading the new poems he was sending them from the Black Sea. Finally, Timrod’s recurrently invoked “A Vision of Poesy” traces in fanciful, mythic guises the curious route that might guide a boy born of “humble parentage” in Charleston, South Carolina, say, or in Duluth, Minnesota, to poetry.

During his incisive entry on Street Legal for The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia, Michael Gray argues that, “Every song deals with love’s betrayal, with Dylan’s being betrayed like Christ, and, head on, with the need to abandon woman’s love.”[31] On Time Out of Mind, and especially “Love and Theft” and Modern Times, art and tradition—I wish to propose—now seize the ground zero once occupied by love, and later God. Dylan always emphasized the traditional footing of his writing. “My songs, what makes them different is that there’s a foundation to them,” he told Jon Pareles. “They’re standing on a strong foundation, and subliminally that’s what people are hearing.”[32] Yet the current intensification of his allusive scale is undeniable.

Without ever winking, Dylan proves canny and sophisticated about all this, though after a fashion that recall’s Laurence Sterne’s celebrated attack on plagiarism, itself plagiarized from The Anatomy of Melancholy. On “Summer Days” from “Love and Theft” Dylan sings:

She’s looking into my eyes, and she’s a-holding my hand

She looking into my eyes, she’s holding my hand,

She says, “You can’t repeat the past,” I say, “You can’t? What do you mean you can’t? Of course, you can.”

His puckish, snaky lines dramatize precisely how one can, in fact, “repeat the past,” since the lyrics slyly reproduce a conversation from The Great Gatsby. [33]On Modern Times, Dylan veers from mediumistic—“I’ve been conjuring up these long dead souls from their crumblin’ tombs”—to self-mocking: “I’m so hard pressed, my mind tied up in knots / I keep recycling the same old thoughts.”

When asked what he believed by David Gates during a 1996 interview in Newsweek, Dylan replied, “I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else. Songs like ‘Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain’ or ‘I Saw the Light’—that’s my religion. I don’t adhere to rabbis, preachers, evangelists, all of that. I’ve learned more from the songs than I’ve learned from any of this kind of entity. The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.”[34] Let’s presume that by “songs” Dylan now also must mean poems, such as Ovid’s or Henry Timrod’s, and novels, such as Fitzgerald’s, along with traditional folk hymns and blues.

Speaking to his 16th century Chinese listeners, Matteo Ricci affirmed the imperative of “good roots or foundation,”[35] and conceived the memory palace he offered them inside a Renaissance visionary architecture that “not only performs the office of conserving for us the things, words and acts which we confide to it . . . but also gives us true wisdom.” [36]

*

In The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, Jonathan Spence quotes Augustine from the Confessions, “Perchance it might be properly said, ‘there be three times; a present of things past, a present of things present, and a present of things future.’”[37] Dylan, too, as far back as his Renaldo and Clara pressed the eternizing powers of art. “The movie creates and holds the time,” he told Jonathan Cott. “That’s what it should do—it should hold that time, breathe in that time and stop time in doing that.”[38] Or, as he again sketched Blood on the Tracks, “Everybody agrees that was pretty different, and what’s different about it is that there’s a code in the lyrics and also there’s no sense of time. There’s no respect for it: you’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there’s little that you can’t imagine not happening.” [39]

In The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci, Jonathan Spence quotes Augustine from the Confessions, “Perchance it might be properly said, ‘there be three times; a present of things past, a present of things present, and a present of things future.’”[37] Dylan, too, as far back as his Renaldo and Clara pressed the eternizing powers of art. “The movie creates and holds the time,” he told Jonathan Cott. “That’s what it should do—it should hold that time, breathe in that time and stop time in doing that.”[38] Or, as he again sketched Blood on the Tracks, “Everybody agrees that was pretty different, and what’s different about it is that there’s a code in the lyrics and also there’s no sense of time. There’s no respect for it: you’ve got yesterday, today and tomorrow all in the same room, and there’s little that you can’t imagine not happening.” [39]

All in the same room. Dylan’s “conjuring,” as he might say, and as Ovid did say, of the dead on Time Out of Mind, “Love and Theft,” and Modern Times stands among the most daring, touching, and original signatures of his art. Who else—or who besides classical Roman poets—writes, has ever written, songs as layered and textured as these? Sheltering the dead among the living, his memory palace tips past into present, but conjurers inevitably summon also the shadows ahead. “Whatever music you love, it didn’t come from nowhere,” Dylan recently advanced on his radio show, and Theme Time Radio Hour is another wing of his memory palace. “It’s always good to know what went down before you, because if you know the past, you can control the future.”[40]

ENDNOTES

[1] Jonathan D. Spence, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci (New York: Penguin, 1984), pp. 1-2

[2] Bob Dylan, Chronicles Volume I (New York, Simon & Schuster, 2004), p. 86

[3] Spence, p. 16

[4] Spence, p. 22

[5] See New York Times for September 14, 2006 and September 17, 2006.

[6] All Timrod quotations are drawn from Poems of Henry Timrod with Memoir and Portrait (B. F. Johnson Publishing Co., Richmond, 1901, and reprinted in facsimile by Kessinger Publishing). Also helpful: Walter Brian Cisco’s Henry Timrod: A Biography (Madison: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2004).

[7] For passages where there are even minor departures between Dylan and Timrod, and when I do not quote the Timrod source elsewhere in this essay, here are the relevant Timrod “originals”: “How then, O weary one! Explain / The sources of that hidden pain?” (“Two Portraits”); “You will perceive that in the breast / The germs of many virtues rest, // Which, ere they feel a lover’s breath, / Lie in a temporary death . . .” (“Two Portraits”); “Ah! Christ forgive us for the crime / Which drowned the memories of the time / In a merely mortal bliss!” (“Our Willie”); “And o’er the city sinks and swells / The chime of old St. Mary’s bells . . .” (“Katie”).

[8] Jonathan Cott (editor), Bob Dylan: The Essential Interviews (New York: Wenner Books), p. 432.

[9] Green’s translations can be found in Ovid, The Erotic Poems (London: Penguin Books, 1982) and Ovid, The Poems of Exile (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). Dylan studied Latin for two years at Hibbing High School, but was Ovid among the authors he translated? During my own sophomore Latin class at Boston College High School, we read the “Pyramis and Thisbe” story from Book IV of The Metamorphoses. It was also at BC High that I first encountered Matteo Ricci, a hero for the Jesuits who taught and resided there, and during a senior year Asian Studies course we were assigned an early biography of the Jesuit missionary to China, Vincent Cronin’s The Wise Man from the West (New York: EP Dutton, 1955). Any mention of “memory” in proximity to Bob Dylan inevitably must also be indebted to Robert Cantwell’s brilliant chapter on Harry Smith and Robert Fludd, “Smith’s Memory Theater,” in When We Were Good (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996). I also benefited from Francis A. Yates’s The Art of Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1966), and an anthology edited by Mary Carruthers and Jan M. Ziolkowski, The Medieval Craft of Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

[10] For two invaluable annotated Dylan websites, see http://republika.pl/bobdylan/mt/ and http://republika.pl/bobdylan/lat/.

[11] Or as these lines and phrases appear in Green’s translations: “The facts demand Censure, the face begs for love—and gets it . . .” (The Amores, Bk. 3, Section 11B); “May the gods grant that my complaint’s unfounded / that I’m wrong in thinking you’ve forgotten me!” (Tristia, Bk. V, Section 13); “Revulsion making you wish you’d never had a woman / And swear you won’t touch one again for years…” (“Cures for Love,” ll.416-7); “…wife dearer to me than myself, you yourself can see . . .” (Tristia, Bk. V, Section 14); “This girl’s got me hooked . . .” (The Amores, Bk. 1, Section 3); and “I want to be with you any way I can . . .” (Tristia, Bk. V, Section 1)

[12] Dylan, Chronicles, pp. 36-37. By referencing “the scary horror tale” (not tales) might he be conflating Ovid (Metamorphoses) and Kafka (The Metamorphosis)? Is this mention of Ovid in Chronicles an early signal of his interest in the Roman poet for Modern Times?

[13] Green, “Introduction” to The Poems of Exile, xix.

[14] Tristia, Bk. II.

[15] Dylan, Chronicles, pp. 92-93.

[16] The Amores, Bk. 1, Section 9.

[17] For the Ovid/Green sources: “Crumbling sepulchers,” etc. from The Amores, Bk. 1, Section 8. “Houseboy,” etc. from The Amores, Bk. 1, Section 8. “Barely enough skin,” etc, from Tristisa, Bk. IV, Section 6 (“I lack my old strength and colour, / there’s barely enough skin to cover my bones . . .”). “Driven from mine,” etc. from Tristia, Bk. I, Section 5.

[18] For the Ovid/Green sources: “’ . . . The bruise on her breast bears witness / To the stain of adultery.’ There his interpretation ended. At those words the blood ran freezing/ From my face, and the world went black before my eyes . . .” (The Amores, Bk. 3, Section 5). “Show mercy, I beg you, shelve your cruel weapons . . .” (Tristia, Bk. II). “You write that I should divert these mournful days with writing . . . Priam, you’re saying, should have fun fresh from his son’s funeral, / or Niobe, bereaved, lead off some cheerful dance . . .” (Tristia¸ Bk. V, Section 12).

[19] As these various lines appear in Ovid/Green: “Catch your opponents sleeping / And unarmed. Just slaughter them where they lie . . .” (The Amores, Book 1, Section 9). “I practice / terms long abandoned, retrace my sullen art’s / ill-fated signs. Thus I drag out my life and time, thus / tear my mind from the contemplation of my woes . . .” (Tristia, Bk. V, Section 7). “[L]oyal and much-loved companions, bonded in brotherhood . . .This may well be my final chance to embrace them—let me make the most of one last extra hour . . .” (Tristia, Bk. I, Section 3). “ . . . even here you’re already familiar to the native tribesmen, / who approve, and share, your code . . .” (Black Sea Letters, Bk. 3, Section 2). “Though I lack such heroic / stature, who says I can’t get heavenly aid / when a god’s angry with me?” (Tristia, Bk. I, Section 2). “The whole house / mourned at my obsequies—men, women, even children, / every nook and corner had its tears . . .” (Tristia, Bk. I, Section 3). “Of this I’ve no doubt—but the very dread of misfortune / often drives me to nurse superfluous fears . . .” (Black Sea Letters¸ Bk. II. Section 7). “Some places make exile/ milder, but there’s no more dismal land than this / beneath either pole. It helps to be near your country’s borders: / I’m in the last outback, at the world’s end . . .” (Black Sea Letters, Bk. II, Section 7).

[20] Ovid on his garden is from Black Sea Letters, Bk. I, Section 8. But Ovid’s garden in “Ain’t Talkin’”? Or Tennyson’s (via “Maud”), as Christopher Ricks proposes? The Garden of Eden? God (or Christ) appears often in the guise of a gardener in Renaissance poems. A case can also be made that the absent gardener at the finish is the singer himself, unconscious (perhaps even dead) after he was “hit from behind” in the opening verse, and presiding over the scene as a ghost.

[21] Cott, 438.

[22] Dylan quoted by Michael Gray in The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia (New York: Continuum, 2006) in his entry on Raeben, p. 561.

[23] T. S. Eliot, “The Waste Land” (1922) in Collected Poems 1909-1962 (New York: Harcourt, 1991), p. 69.

[24] Frank Bidart, “The Second Hour of the Night,” in Desire (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux), p. 46.

[25] Junichi Saga, Confessions of a Yakuza (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1991), pp. 153-4. The Dylan lines, from “Floater (Too Much to Ask),” run: “Never seen him quarrel with my mother even once/ Things come alive or they fall flat.”

[26] Dylan, p. 86.

[27] Tristia, Bk. IV, Section 6.

[28] Timrod, from “Our Willie”: “By that sweet grave, in that dark room,/ We may weave at will for each other’s ear,/ Of that life, and that love, and that early doom/ The tale which is shadowed here…”

[29] “…I’m barred from relaxation/ in a place ringed by countless foes.” (Tristia, Bk. V, Section 12). Also see above, Note 13.

[30] Tristia, Bk. V, Section 7.

[31] Gray, p. 643.

[32] Cott, p. 396.

[33] F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (1925). As Nick says of Gatsby in Chapter 6:

“He broke off and began to walk up and down a desolate path of fruit rinds and discarded favors and crushed flowers.

‘I wouldn’t ask too much of her,’ I ventured. ‘You can’t repeat the past.’

‘Can’t repeat the past?’ he cried incredulously. ‘Why of course you can!’

He looked around him wildly, as if the past were lurking here in the shadow of his house, just out of reach of his hand.”

[34] David Gates, “Dylan Revisited,” reprinted in Studio A: The Bob Dylan Reader, edited by Benjamin Hedin (New York: Norton, 2004), p. 236.

[35] Spence, p. 146.

[36] Spence, p. 20. He is quoting Guilio Camillo (Delminio) on his 16th century “memory theatre.”

[37] Spence, p. 16.

[38] Cott, p. 192.

[39] Cott, p. 260.

[40] Dylan quoted in MOJO, April, 2007. p. 34

Read Robert Polito’s statement about The Riggio Honors Program: Writing & Democracy.

Robert Polito, Director of Writing Programs; Professor of Writing, PhD, English Romanticism, Harvard University

Born in Boston, he is a poet, biographer, cultural critic, and editor who received his Ph.D. in English and American Language and Literature from Harvard. His most recent books are the poetry collection Hollywood & God, which was selected one of the top five poetry books of the year by Barnes and Noble, The Complete Film Writings of Manny Farber (editor), and David Goodis: Five Noir Novels of the 1940s and 50s (editor). His other books include Savage Art: A Biography of Jim Thompson, which received the National Book Critics Circle Award and an Edgar; Doubles (a book of poems); A Reader’s Guide to James Merrill’s The Changing Light at Sandover; and At the Titan’s Breakfast: Three Essays on Byron’s Poetry. He is also the editor Library of America volumes Crime Novels: American Noir of the 30s and 40s, Crime Novels: American Noir of the 50s, and The Selected Poems of Kenneth Fearing, as well as the editor of The Everyman James M. Cain and The Everyman Dashiell Hammett.

His essays and poems have appeared in Best American Poetry, Best American Essays, and Best American Film Writing, and numerous literature, film, and music anthologies, including Poems of New York, O.K. You Mugs, 110 Stories: New York Writers After September 11, The Cambridge Companion to Bob Dylan, and This Is Pop: In Search of the Elusive at The Experience Music Project. He contributed catalog essays to Manny Farber: About Face, and Patricia Patterson: Here and There, Back and Forth.

His work also has been published in many magazines, including the New Yorker, Harper’s, the Yale Review, Art Forum, Bookforum, Black Clock, the LA Times Book Review, the Boston Globe, The Poetry Foundation Website, LIT, BOMB, Open City, Ploughshares, the New York Times Book Review, AGNI, and the Los Angeles Review of Books, among others.

Polito judges the annual Graywolf Nonfiction Book Prize, and has received fellowships from the Ingram Merrill and the John Simon Guggenheim Foundations. He is a contributing editor at BOMB, Fence, LIT, and The Boston Review, and serves on the advisory boards of Cave Canem and the Flow Chart Foundation.

He has previously taught at Harvard, Wellesley, and New York University. At the New School, Polito is the founding Director of the MFA Program in Creative Writing, and the originator (with Len Riggio) of the Len and Louise Riggio Writing & Democracy Program and of ASHLAB, a digital mapping project involving John Ashbery’s Hudson, New York house and his poetry. Current book project: Detours: Seven Noir Lives (forthcoming Knopf).

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

- Categories →

- Faculty

- Works

Portfolio

-

Frontiersville

-

Civic Engagement / Luis Jaramillo

-

Elizabeth Gaffney in Conversation with Jessica Sennett

-

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

-

Literature in Evolution / Lena Valencia

-

Transmissions: The Literature of Aids / Josué Rivera

-

Four Poems / Catherine Barnett

-

Christopher Pugh: To Colorado

-

Animal Farm: Timeline & Bias / John Reed

-

She Hath Writ Diligently Her Own Mind: Elizabeth Childers / Bean Haskell

-

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

-

Ari Spool: Bricks

-

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

-

Conrad Hamanaka Yama / Zoe Rivka Panagopoulos & Ricky Tucker

-

Community

-

Class Stories

-

No Scripts / Bean Haskell

-

Spring’s Last Words: Riggio Student Reading / Ashawnta Jackson

-

GPS / Patricia Carlin

-

Midway / Laura Cronk

-

A Certain Rainy Day / Zia Jaffrey

-

The Story Prize

-

The Next Flight / Jefferey Renard Allen

-

The Inquisitive Eater Blog First Year Anniversary: March 18, 2013 / Jessica Sennett

-

Riggio Forum: Sean Howe / Natassja Schiel & Jessica Sennett

-

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

-

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

-

Nonfiction Forum: Tom Lutz / Ashawnta Jackson & Nico Rosario

-

Homage to Bill McKibben / Suzannah Lessard

-

The Unsolved Mystery of “Epitaph to a Love” by Mildred Green, 1948 / Jessica Sennett

-

Dancing About Writing