He Saw Me

Ricky Tucker

I’m sitting on a panel. It’s almost my turn in a line up of New School regulars: faculty, staff, students—both alum and current, prospective students in the audience. It’s a bit of a blur what was said before me and before I know it, I’m being handed a mic. I lean in.

“The question is, ‘How did I get here?’”

I explain to them how I had worked a full time job in admissions at a university in Boston and how the irony of admitting kids into college and not having a degree myself started nagging at me. I related the conversation when I voiced those concerns to my boss—how going to school at night, albeit for free, was taking too long—and she responded,“Oh, don’t worry, it’ll only take you ten years,” to which I then replied “No it won’t.” I told them about my back knowledge of The New School and how the names and ideas attached to it always drew me in—names like Baldwin, Kerouac, Cage, Graham. But it was the curriculum that really did it for me. When I got into the Riggio: Writing and Democracy program, my first choice, I made arrangements to move, leaving behind an unopened, and by that point, inconsequential decision letter from Hunter College. One of the best instinctual decisions I’ve ever made.

Part of the admissions essay was to look at the Riggio curriculum and pick a dream schedule, a difficult challenge because upon inspection, I had wanted to take everything in the course catalogue. But I had to pick something, and first on that list was Greil Marcus’s lecture, Old Weird America, and when I started my first semester at The New School, it was my first class.

Not only was it remarkable to be physically sitting there in the construct I had formulated in my head—living the dream, so to speak—but also the class was stunning. It was an exploration of folk/blues tropes, primarily through the lens of Bob Dylan. At the time, I was also taking a Eugene Lang course called Vogue’ology, which was half Vogue dance technique and the other half cultural theory on the Vogue/Ballroom scene of Harlem, the birthplace of Vogue. The terrain these courses covered was staggering, but what struck me most were the intersections in theory between these two classes—how Folk and Vogue both came out of disenfranchised and marginalized groups, how the famine and high infant mortality of the Dust Bowl of the ’30s matched the AIDS crisis that hit New York in the ’80s, how art forms spring up out of ashes.

So for my finals for both classes I wrote a murder ballad for Dorian Corey, famous drag queen and verbose narrator of the film Paris Is Burning. Incidentally, Corey was also known for having killed an intruder in her home and keeping, for some 20-odd years, the mummified body, which wasn’t discovered until Corey’s death. In traditional folk song fashion, I took quotes form Corey herself, news clippings about the murder, and Vogue elements like Egyptian hieroglyphics and the term shade, to create lyrics. I wrote and played the violin part to the song and my friend and fellow North Carolinian, Candace Miller, sang my words and played guitar. The finals went well, but more than anything, I realized how all-inclusive my education had become. I was suddenly creating art that was utilizing all of my interests. I saw how every class in the Riggio curriculum was exploring contemporary issues, themes crisscrossing all over the place.

And it happens again and again. This fall I took two courses: Queer NYC and Solo Theater, the first just because and the other to infuse conviction into my readings, to not let the amount of stress of talking up in front of people exceed the oomph of my prose, draining my words of their power. For that class, my final performance was a confessional-style solo piece about a whirlwind love I had with a South African the summer before. It started with me and a chair, and it ended with a dance performance, one part Vogue and two parts Modern, I’d say.

Meanwhile, back in Ricardo Montez’s Queer NYC course, we learned about Queering a space, how certain actions, however casual, rote, or subversive, can change a space into a place. We hit on the fact that New York isn’t the same New York that had queers livening the piers at night, Voguers sashaying through the almost curtained arch of Washington Square Park. So as part of my final, I took that dance from solo my piece, the one about gay love, and performed it in Washington Square as a ritualistic act of transgression, thereby queering the space. I realized after watching the video that my NYPD sweatshirt underscored the defiant act. These are the types of happy accidents we pray for, the ones that bring it all together and add an extra page of theory to your final paper. Very New School.

Since I started the Riggio program I’ve not only become more engaged academically, but as a writer and an artist, I’ve walked in my theory. In Greil Marcus’s class we read John Henry Days by Colson Whitehead, and a year later I had the privilege of sharing a stage with him at a reading for the 12th Street launch, which I’m an editor for. I participated in the Whitney Biennial last year as part of a sound art investigation that explored the connection between audio and freedom. I’ve worked with and collaborated with artists I respect, I’ve been challenged, and I’ve been granted opportunities I didn’t even know existed. So for me, in the grand scheme of things, how I got here isn’t nearly as interesting as what happened once I did.

Ricky Tucker is an art critic, editor, and short-storyteller. He can quote Designing Women but not Shakespeare.

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

- Categories →

- Media

- Students

- Works

Portfolio

-

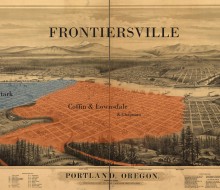

Frontiersville

-

Civic Engagement / Luis Jaramillo

-

Elizabeth Gaffney in Conversation with Jessica Sennett

-

A Trip to Hibbing High / Greil Marcus

-

Literature in Evolution / Lena Valencia

-

Transmissions: The Literature of Aids / Josué Rivera

-

Four Poems / Catherine Barnett

-

Christopher Pugh: To Colorado

-

Animal Farm: Timeline & Bias / John Reed

-

She Hath Writ Diligently Her Own Mind: Elizabeth Childers / Bean Haskell

-

Bob Dylan’s Memory Palace / Robert Polito

-

Ari Spool: Bricks

-

Revisiting the Final Years of Béla Bartók / Liben Eabisa

-

Conrad Hamanaka Yama / Zoe Rivka Panagopoulos & Ricky Tucker

-

Community

-

Class Stories

-

No Scripts / Bean Haskell

-

Spring’s Last Words: Riggio Student Reading / Ashawnta Jackson

-

GPS / Patricia Carlin

-

Midway / Laura Cronk

-

A Certain Rainy Day / Zia Jaffrey

-

The Story Prize

-

The Next Flight / Jefferey Renard Allen

-

The Inquisitive Eater Blog First Year Anniversary: March 18, 2013 / Jessica Sennett

-

Riggio Forum: Sean Howe / Natassja Schiel & Jessica Sennett

-

Down the Manhole / Elizabeth Gaffney

-

He Saw Me / Ricky Tucker

-

Nonfiction Forum: Tom Lutz / Ashawnta Jackson & Nico Rosario

-

Homage to Bill McKibben / Suzannah Lessard

-

The Unsolved Mystery of “Epitaph to a Love” by Mildred Green, 1948 / Jessica Sennett

-

Dancing About Writing